You and a friend are driving in a car. You’ve almost reached an intersection. The stoplight turns red.

My teacher had handwritten the narrative on my twelfth-grade physics midterm. Many mechanics problems involve cars: Drivers smash into each other at this angle or that angle, interlocking their vehicles. The Principle of Conservation of Linear Momentum governs how the wreck moves. Students deduce how quickly the wreck skids, and in which direction.

Few mechanics problems involve the second person. I have almost reached an intersection?

You’re late for an event, and stopping would cost you several minutes. What do you do?

We’re probably a few meters from the light, I thought. How quickly are we driving? I could calculate the acceleration needed to—

(a) Speed through the red light.

(b) Hit the brakes. Fume about missing the light while you wait.

(c) Stop in front of the intersection. Chat with your friend, making the most of the situation. Resolve to leave your house earlier next time.

Pencils scritched, and students shifted in their chairs. I looked up from the choices.

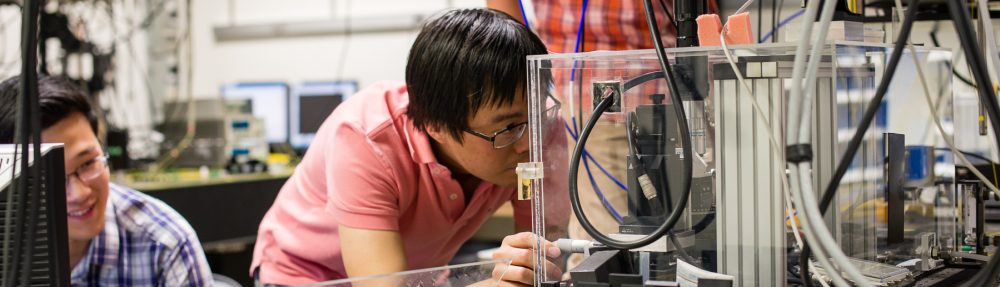

Our classroom differed from most high-school physics classrooms. Sure, posters about Einstein and Nobel prizes decorated the walls. Circuit elements congregated in a corner. But they didn’t draw the eye the moment one stepped through the doorway.

A giant yellow smiley face did.

It sat atop the cupboards that faced the door. Next to the smiley stood a placard that read, “Say please and thank you.” Another placard hung above the chalkboard: “Are you showing your good grace and character?”

Our instructor taught mechanics and electromagnetism. He wanted to teach us more. He pronounced the topic in a southern sing-song: “an attitude of gratitude.”

Teenagers populate high-school classrooms. The cynicism in a roomful of teenagers could have rivaled the cynicism in Hemingway’s Paris. Students regarded his digressions as oddities. My high school fostered more manners than most. But a “Can you believe…?” tone accompanied recountings of the detours.

Yet our teacher’s drawl held steady as he read students’ answers to a bonus question on a test (“What are you grateful for?”). He bade us gaze at a box of Wheaties—the breakfast of champions—on whose front hung a mirror. He awarded Symbolic Lollipops for the top grades on tests and for acts of kindness. All with a straight face.

Except, once or twice over the years, I thought I saw his mouth tweak into a smile.

I’ve puzzled out momentum problems since graduating from that physics class. I haven’t puzzled out how to regard the class. As mawkish or moral? Heroic or humorous? I might never answer those questions. But the class led me toward a career in physics, and physicists value data. One datum stands out: I didn’t pack my senior-year high-school physics midterm when moving to Pasadena. But the midterm remains with me.