I used to eat lunch at the foundations-of-quantum-theory table.

I was a Masters student at the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics, where I undertook a research project during the spring term. The project squatted on the border between quantum information theory and quantum foundations, where my two mentors worked. Quantum foundations concerns how quantum physics differs from classical physics; which alternatives to quantum physics could govern our world but don’t; and those questions, such as about Schrödinger’s cat, that fascinate us when we first encounter quantum theory, that many advisors warn probably won’t land us jobs if we study them, and that most physicists argue about only over a beer in the evening.

I don’t drink beer, so I had to talk foundations over sandwiches around noon.

One of us would dream up what appeared to be a perpetual-motion machine; then the rest of us would figure out why it couldn’t exist. Satisfied that the second law of thermodynamics still reigned, we’d decamp for coffee. (Perpetual-motion machines belong to the foundations of thermodynamics, rather than the foundations of quantum theory, but we didn’t discriminate.) I felt, at that lunch table, an emotion blessed to a student finding her footing in research, outside her country of origin: belonging.

The quantum-foundations lunch table came to mind last month, when I learned that Britain’s Institute of Physics had selected me to receive its International Quantum Technology Emerging Researcher Award. I was very grateful for the designation, but I was incredulous: Me? Technology? But I began grad school at the quantum-foundations lunch table. Foundations is to technology as the philosophy of economics is to dragging a plow across a wheat field, at least stereotypically.

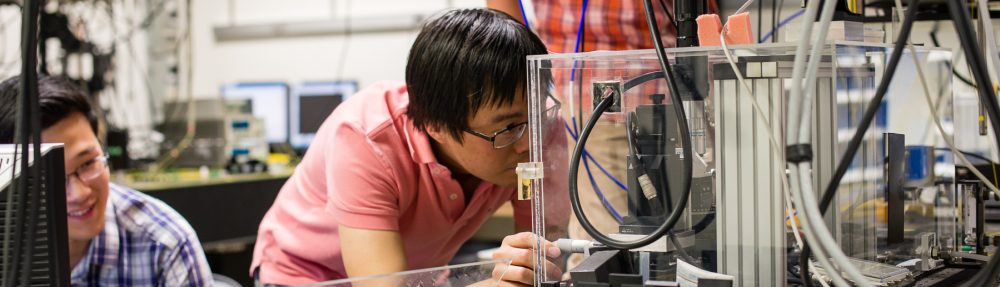

Worse, I drag plows from wheat field to barley field to oat field. I’m an interdisciplinarian who never belongs in the room I’ve joined. Among quantum information theorists, I’m the thermodynamicist, or that theorist who works with experimentalists; among experimentalists, I’m the theorist; among condensed-matter physicists, I’m the quantum information theorist; among high-energy physicists, I’m the quantum information theorist or the atomic-molecular-and-optical (AMO) physicist; and, among quantum thermodynamicists, I do condensed matter, AMO, high energy, and biophysics. I usually know less than everyone else in the room about the topic under discussion. An interdisciplinarian can leverage other fields’ tools to answer a given field’s questions and can discover questions. But she may sound, to those in any one room, as though she were born yesterday. As Kermit the Frog said,

Grateful as I am, I’d rather not dwell on why the Institute of Physics chose my file; anyone interested can read the citation or watch the thank-you speech. But the decision turned out to involve foundations and interdisciplinarity. So I’m dedicating this article to two sources of inspiration: an organization that’s blossomed by crossing fields and an individual who’s driven technology by studying fundamentals.

Britain’s Institute for Physics has a counterpart in the American Physical Society. The latter has divisions, each dedicated to some subfield of physics. If you belong to the society and share an interest in one of those subfields, you can join that division, attend its conferences, and receive its newsletters. I learned about Division of Soft Matter from this article, which I wish I could quote almost in full. This division’s members study “a staggering variety of materials from the everyday to the exotic, including polymers such as plastics, rubbers, textiles, and biological materials like nucleic acids and proteins; colloids, a suspension of solid particles such as fogs, smokes, foams, gels, and emulsions; liquid crystals like those found in electronic displays; [ . . . ] and granular materials.” Members belong to physics, chemistry, biology, engineering, and geochemistry.

Despite, or perhaps because of, its interdisciplinarity, the division has thrived. The group grew from a protodivision (a “topical group,” in the society’s terminology) to a division in five years—at “an unprecedented pace.” Intellectual diversity has complemented sociological diversity: The division “ranks among the top [American Physical Society] units in terms of female membership.” The division’s chair observes a close partnership between theory and experiment in what he calls “a vibrant young field.”

And some division members study oobleck. Wouldn’t you like to have an excuse to say “oobleck” every day?

The second source of inspiration lives, like the Institute of Physics, in Britain. David Deutsch belongs at the quantum-foundations table more than I. A theoretical physicist at Oxford, David cofounded the field of quantum computing. He explained why to me in a fusion of poetry and the pedestrian: He was “fixing the roof” of quantum theory. As a graduate student, David wanted to understand quantum foundations—what happens during a measurement—but concluded that quantum theory has too many holes. The roof was leaking through those holes, so he determined to fix them. He studied how information transformed during quantum processes, married quantum theory with computer science, and formalized what quantum computers could and couldn’t accomplish. Which—years down the road, fused with others’ contributions—galvanized experimentalists to harness ions and atoms, improve lasers and refrigerators, and build quantum computers and quantum cryptography networks.

David is a theorist and arguably a philosopher. But he’d have swept the Institute of Physics’s playing field, could he have qualified as an “emerging researcher” this autumn (David began designing quantum algorithms during the 1980s).

I returned to the Perimeter Institute during the spring term of 2019. I ate lunch at the quantum-foundations table, and I felt that I still belonged. I feel so still. But I’ve eaten lunch at other tables by now, and I feel that I belong at them, too. I’m grateful if the habit has been useful.

Congratulations to Hannes Bernien, who won the institute’s International Quantum Technology Young Scientist Award, and to the “highly commended” candidates, whom you can find here!