Xi Dong, Alex Maloney, Henry Maxfield and I recently posted a paper to the arXiv with the title: Phase Transitions in 3D Gravity and Fractal Dimension. In other words, we’ll get about ten readers per year for the next few decades. Despite the heady title, there’s deep geometrical beauty underlying this work. In this post I want to outline the origin story and motivation behind this paper.

There are two different branches to the origin story. The first was my personal motivation and the second is related to how I came into contact with my collaborators (who began working on the same project but with different motivation, namely to explain a phase transition described in this paper by Belin, Keller and Zadeh.)

During the first year of my PhD at Caltech I was working in the mathematics department and I had a few brief but highly influential interactions with Nikolai Makarov while I was trying to find a PhD advisor. His previous student, Stanislav Smirnov, had recently won a Fields Medal for his work studying Schramm-Loewner evolution (SLE) and I was captivated by the beauty of these objects.

SLE example from Scott Sheffield’s webpage. SLEs are the fractal curves that form at the interface of many models undergoing phase transitions in 2D, such as the boundary between up and down spins in a 2D magnet (Ising model.)

One afternoon, I went to Professor Makarov’s office for a meeting and while he took a brief phone call I noticed a book on his shelf called Indra’s Pearls, which had a mesmerizing image on its cover. I asked Professor Makarov about it and he spent 30 minutes explaining some of the key results (which I didn’t understand at the time.) When we finished that part of our conversation Professor Makarov described this area of math as “math for the future, ahead of the tools we have right now” and he offered for me to borrow his copy. With a description like that I was hooked. I spent the next six months devouring this book which provided a small toehold as I tried to grok the relevant mathematics literature. This year or so of being obsessed with Kleinian groups (the underlying objects in Indra’s Pearls) comes back into the story soon. I also want to mention that during that meeting with Professor Makarov I was exposed to two other ideas that have driven my research as I moved from mathematics to physics: quasiconformal mappings and the simultaneous uniformization theorem, both of which will play heavy roles in the next paper I release. In other words, it was a pretty important 90 minutes of my life.

Google image search for “Indra’s Pearls”. The math underlying Indra’s Pearls sits at the intersection of hyperbolic geometry, complex analysis and dynamical systems. Mathematicians oftentimes call this field the study of “Kleinian groups”. Most of these figures were obtained by starting with a small number of Mobius transformations (usually two or three) and then finding the fixed points for all possible combinations of the initial transformations and their inverses. Indra’s Pearls was written by David Mumford, Caroline Series and David Wright. I couldn’t recommend it more highly.

My life path then hit a discontinuity when I was recruited to work on a DARPA project, which led to taking an 18 month leave of absence from Caltech. It’s an understatement to say that being deployed in Afghanistan led to extreme introspection. While “down range” I had moments of clarity where I knew life was too short to work on anything other than ones’ deepest passions. Before math, the thing that got me into science was a childhood obsession with space and black holes. I knew that when I returned to Caltech I wanted to work on quantum gravity with John Preskill. I sent him an e-mail from Afghanistan and luckily he was willing to take me on as a student. But as a student in the mathematics department, I knew it would be tricky to find a project that involved all of: black holes (my interest), quantum information (John’s primary interest at the time) and mathematics (so I could get the degree.)

I returned to Caltech in May of 2012 which was only two months before the Firewall Paradox was introduced by Almheiri, Marolf, Polchinski and Sully. It was obvious that this was where most of the action would be for the next few years so I spent a great deal of time (years) trying to get sharp enough in the underlying concepts to be able to make comments of my own on the matter. Black holes are probably the closest things we have in Nature to the proverbial bottomless pit, which is an apt metaphor for thinking about the Firewall Paradox. After two years I was stuck. I still wasn’t close to confident enough with AdS/CFT to understand a majority of the promising developments. And then at exactly the right moment, in the summer of 2014, Preskill tipped my hat to a paper titled Multiboundary Wormholes and Holographic Entanglement by Balasubramanian, Hayden, Maloney, Marolf and Ross. It was immediately obvious to me that the tools of Indra’s Pearls (Kleinian groups) provided exactly the right language to study these “multiboundary wormholes.” But despite knowing a bridge could be built between these fields, I still didn’t have the requisite physics mastery (AdS/CFT) to build it confidently.

Before mentioning how I met my collaborators and describing the work we did together, let me first describe the worlds that we bridged together.

3D Gravity and Universality

As the media has sensationalized to death, one of the most outstanding questions in modern physics is to discover and then understand a theory of quantum gravity. As a quick aside, Quantum gravity is just a placeholder name for such a theory. I used italics because physicists have already discovered candidate theories, such as string theory and loop quantum gravity (I’m not trying to get into politics, just trying to demonstrate that there are multiple candidate theories). But understanding these theories — carrying out all of the relevant computations to confirm that they are consistent with Nature and then doing experiments to verify their novel predictions — is still beyond our ability. Surprisingly, without knowing the specific theory of quantum gravity that guides Nature’s hand, we’re still able to say a number of universal things that must be true for any theory of quantum gravity. The most prominent example being the holographic principle which comes from the entropy of black holes being proportional to the surface area encapsulated by the black hole’s horizon (a naive guess says the entropy should be proportional to the volume of the black hole; such as the entropy of a glass of water.) Universal statements such as this serve as guideposts and consistency checks as we try to understand quantum gravity.

It’s exceedingly rare to find universal statements that are true in physically realistic models of quantum gravity. The holographic principle is one such example but it pretty much stands alone in its power and applicability. By physically realistic I mean: 3+1-dimensional and with the curvature of the universe being either flat or very mildly positively curved. However, we can make additional simplifying assumptions where it’s easier to find universal properties. For example, we can reduce the number of spatial dimensions so that we’re considering 2+1-dimensional quantum gravity (3D gravity). Or we can investigate spacetimes that are negatively curved (anti-de Sitter space) as in the AdS/CFT correspondence. Or we can do BOTH! As in the paper that we just posted. The hope is that what’s learned in these limited situations will back-propagate insights towards reality.

The motivation for going to 2+1-dimensions is that gravity (general relativity) is much simpler here. This is explained eloquently in section II of Steve Carlip’s notes here. In 2+1-dimensions, there are no “local”/”gauge” degrees of freedom. This makes thinking about quantum aspects of these spacetimes much simpler.

The standard motivation for considering negatively curved spacetimes is that it puts us in the domain of AdS/CFT, which is the best understood model of quantum gravity. However, it’s worth pointing out that our results don’t rely on AdS/CFT. We consider negatively curved spacetimes (negatively curved Lorentzian manifolds) because they’re related to what mathematicians call hyperbolic manifolds (negatively curved Euclidean manifolds), and mathematicians know a great deal about these objects. It’s just a helpful coincidence that because we’re working with negatively curved manifolds we then get to unpack our statements in AdS/CFT.

Multiboundary wormholes

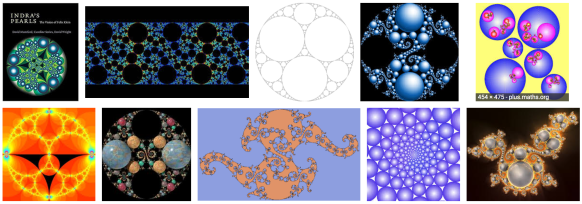

Finding solutions to Einstein’s equations of general relativity is a notoriously hard problem. Some of the more famous examples include: Minkowski space, de-Sitter space, anti-de Sitter space and Schwarzschild’s solution (which describes perfectly symmetrical and static black holes.) However, there’s a trick! Einstein’s equations only depend on the local curvature of spacetime while being insensitive to global topology (the number of boundaries and holes and such.) If M is a solution of Einstein’s equations and is a discrete subgroup of the isometry group of

, then the quotient space

will also be a spacetime that solves Einstein’s equations! Here’s an example for intuition. Start with 2+1-dimensional Minkowski space, which is just a stack of flat planes indexed by time. One example of a “discrete subgroup of the isometry group” is the cyclic group generated by a single translation, say the translation along the x-axis by ten meters. Minkowski space quotiented by this group will also be a solution of Einstein’s equations, given as a stack of 10m diameter cylinders indexed by time.

Start with 2+1-dimensional Minkowski space which is just a stack of flat planes index by time. Think of the planes on the left hand side as being infinite. To “quotient” by a translation means to glue the green lines together which leaves a cylinder for every time slice. The figure on the right shows this cylinder universe which is also a solution to Einstein’s equations.

D+1-dimensional Anti-de Sitter space () is the maximally symmetric d+1-dimensional Lorentzian manifold with negative curvature. Our paper is about 3D gravity in negatively curved spacetimes so our starting point is

which can be thought of as a stack of Poincare disks (or hyperbolic sheets) with the time dimension telling you which disk (sheet) you’re on. The isometry group of

is a group called

which in turn is isomorphic to the group

. The group

isn’t a very common group but a single copy of

is a very well-studied group. Discrete subgroups of it are called Fuchsian groups. Every element in the group should be thought of as a 2×2 matrix which corresponds to a Mobius transformation of the complex plane. The quotients that we obtain from these Fuchsian groups, or the larger isometry group yield a rich infinite family of new spacetimes, which are called multiboundary wormholes. Multiboundary wormholes have risen in importance over the last few years as powerful toy models when trying to understand how entanglement is dispersed near black holes (Ryu-Takayanagi conjecture) and for how the holographic dictionary works in terms of mapping operators in the boundary CFT to fields in the bulk (entanglement wedge reconstruction.)

Three dimensional AdS can be thought of as a stack of hyperboloids indexed by time. It’s convenient to use the Poincare disk model for the hyperboloids so that the entire spacetime can be pictured in a compact way. Despite how things appear, all of the triangles have the same “area”.

I now want to work through a few examples.

BTZ black hole: this is the simplest possible example. It’s obtained by quotienting by a cyclic group

, generated by a single matrix

which for example could take the form

. The matrix A acts by fractional linear transformation on the complex plane, so in this case the point

gets mapped to

. In this case

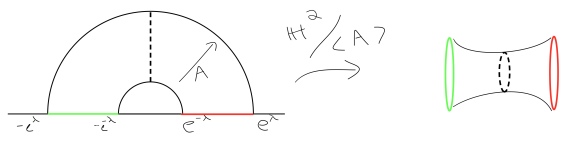

Start with as a stack of hyperbolic half planes indexed by time. A quotient by A means that each hyperbolic half plane gets quotiented. Quotienting a constant time slice by the map

gives a surface that’s topologically a cylinder. Using the picture above this means you glue together the solid black curves. The green and red segments become two boundary regions. We call it the BTZ black hole because when you add “time” it becomes impossible to send a signal from the green boundary to the red boundary, or vica versa. The dotted line acts as an event horizon.

Three boundary wormhole:

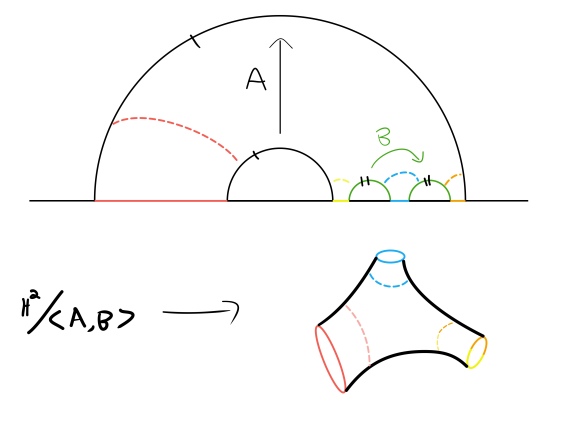

There are many parameterizations that we can choose to obtain the three boundary wormhole. I’ll only show schematically how the gluings go. A nice reference with the details is this paper by Henry Maxfield.

This is a picture of a constant time slice of quotiented by the A and B above. Each time slice is given as a copy of the hyperbolic half plane with the black arcs and green arcs glued together (by the maps A and B). These gluings yield a pair of pants surface. Each of the boundary regions are causally disconnected from the others. The dotted lines are black hole horizons that illustrate where the causal disconnection happens.

Torus wormhole:

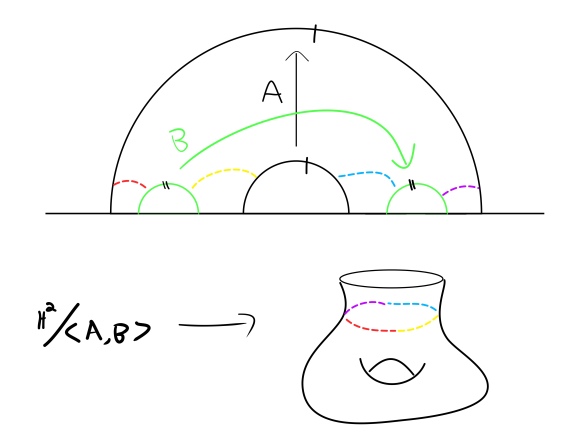

It’s simpler to write down generators for the torus wormhole; but following along with the gluings is more complicated. To obtain the three boundary wormhole we quotient by the free group

where

and

. (Note that this is only one choice of generators, and a highly symmetrical one at that.)

This is a picture of a constant time slice of quotiented by the A and B above. Each time slice is given as a copy of the hyperbolic half plane with the black arcs and green arcs glued together (by the maps A and B). These gluings yield what’s called the “torus wormhole”. Topologically it’s just a donut with a hole cut out. However, there’s a causal structure when you add time to the mix where the dotted lines act as a black hole horizon, so that a message sent from behind the horizon will never reach the boundary.

Lorentzian to Euclidean spacetimes

So far we have been talking about negatively curved Lorentzian manifolds. These are manifolds that have a notion of both “time” and “space.” The technical definition involves differential geometry and it is related to the signature of the metric. On the other hand, mathematicians know a great deal about negatively curved Euclidean manifolds. Euclidean manifolds only have a notion of “space” (so no time-like directions.) Given a multiboundary wormhole, which by definition, is a quotient of where

is a discrete subgroup of Isom(

), there’s a procedure to analytically continue this to a Euclidean hyperbolic manifold of the form

where

is three dimensional hyperbolic space and

is a discrete subgroup of the isometry group of

, which is

. This analytic continuation procedure is well understood for time-symmetric spacetimes but it’s subtle for spacetimes that don’t have time-reversal symmetry. A discussion of this subtlety will be the topic of my next paper. To keep this blog post at a reasonable level of technical detail I’m going to need you to take it on a leap of faith that to every Lorentzian 3-manifold multiboundary wormhole there’s an associated Euclidean hyperbolic 3-manifold. Basically you need to believe that given a discrete subgroup

of

there’s a procedure to obtain a discrete subgroup

of

. Discrete subgroups of

are called Kleinian groups and quotients of

by groups of this form yield hyperbolic 3-manifolds. These Euclidean manifolds obtained by analytic continuation arise when studying the thermodynamics of these spacetimes or also when studying correlation functions; there’s a sense in which they’re physical.

TLDR: you start with a 2+1-d Lorentzian 3-manifold obtained as a quotient and analytic continuation gives a Euclidean 3-manifold obtained as a quotient

where

is 3-dimensional hyperbolic space and

is a discrete subgroup of

(Kleinian group.)

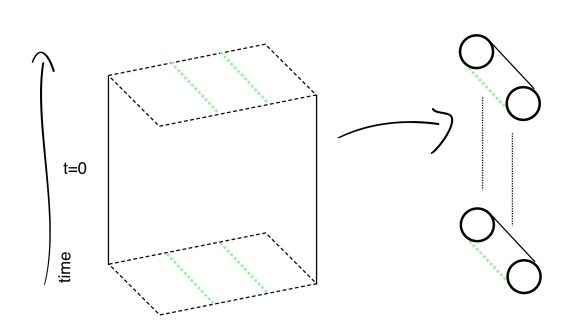

Limit sets:

Every Kleinian group has a fractal that’s naturally associated with it. The fractal is obtained by finding the fixed points of every possible combination of generators and their inverses. Moreover, there’s a beautiful theorem of Patterson, Sullivan, Bishop and Jones that says the smallest eigenvalue

of the spectrum of the Laplacian on the quotient Euclidean spacetime

is related to the Hausdorff dimension of this fractal (call it

) by the formula

. This smallest eigenvalue controls a number of the quantities of interest for this spacetime but calculating it directly is usually intractable. However, McMullen proposed an algorithm to calculate the Hausdorff dimension of the relevant fractals so we can get at the spectrum efficiently, albeit indirectly.

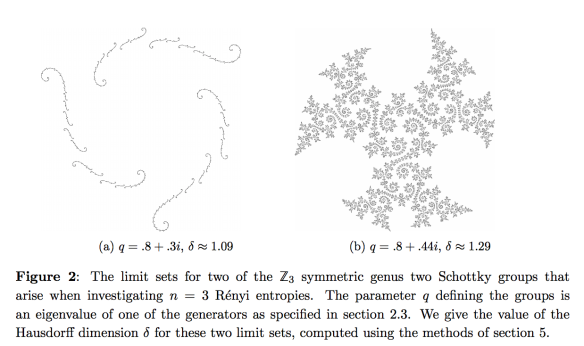

This is a screen grab of Figure 2 from our paper. These are two examples of fractals that emerge when studying these spacetimes. Both of these particular fractals have a 3-fold symmetry. They have this symmetry because these particular spacetimes came from looking at something called “n=3 Renyi entropies”. The number q indexes a one complex dimensional family of spacetimes that have this 3-fold symmetry. These Kleinian groups each have two generators that are described in section 2.3 of our paper.

What we did

Our primary result is a generalization of the Hawking-Page phase transition for multiboundary wormholes. To understand the thermodynamics (from a 3d quantum gravity perspective) one starts with a fixed boundary Riemann surface and then looks at the contributions to the partition function from each of the ways to fill in the boundary (each of which is a hyperbolic 3-manifold). We showed that the expected dominant contributions, which are given by handlebodies, are unstable when the kinetic operator is negative, which happens whenever the Hausdorff dimension of the limit set of

is greater than the lightest scalar field living in the bulk. One has to go pretty far down the quantum gravity rabbit hole (black hole) to understand why this is an interesting research direction to pursue, but at least anyone can appreciate the pretty pictures!