An 81-year-old medical doctor has fallen off a ladder in his house. His pet bird hopped out of his reach, from branch to branch of a tree on the patio. The doctor followed via ladder and slipped. His servants cluster around him, the clamor grows, and he longs for his wife to join him before he dies. She arrives at last. He gazes at her face; utters, “Only God knows how much I loved you”; and expires.

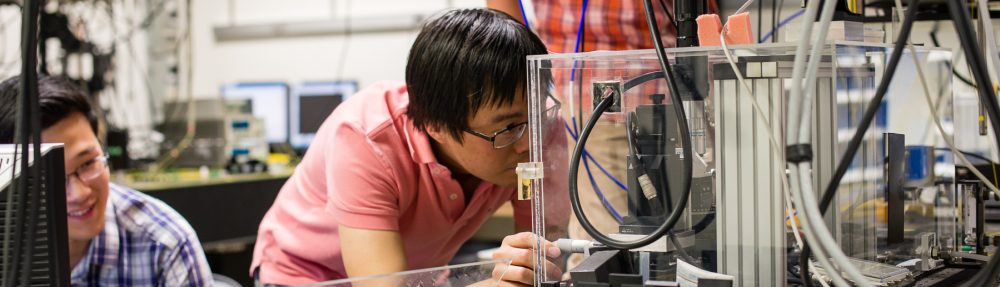

I set the book down on my lap and looked up. I was nestled in a wicker chair outside the Huntington Art Gallery in San Marino, California. Busts of long-dead Romans kept me company. The lawn in front of me unfurled below a sky that—unusually for San Marino—was partially obscured by clouds. My final summer at Caltech was unfurling. I’d walked to the Huntington, one weekend afternoon, with a novel from Caltech’s English library.1

What a novel.

You may have encountered the phrase “love in the time of corona.” Several times. Per week. Throughout the past six months. Love in the Time of Cholera predates the meme by 35 years. Nobel laureate Gabriel García Márquez captured the inhabitants, beliefs, architecture, mores, and spirit of a Colombian city around the turn of the 20th century. His work transcends its setting, spanning love, death, life, obsession, integrity, redemption, and eternity. A thermodynamicist couldn’t ask for more-fitting reading.

Love in the Time of Cholera centers on a love triangle. Fermina Daza, the only child of a wealthy man, excels in her studies. She holds herself with poise and self-assurance, and she spits fire whenever others try to control her. The girl dazzles Florentino Ariza, a poet, who restructures his life around his desire for her. Fermina Daza’s pride impresses Dr. Juvenal Urbino, a doctor renowned for exterminating a cholera epidemic. After rejecting both men, Fermina Daza marries Dr. Juvenal Urbino. The two personalities clash, and one betrays the other, but they cling together across the decades. Florentino Ariza retains his obsession with Fermina Daza, despite having countless affairs. Dr. Juvenal Urbino dies by ladder, whereupon Florentino Ariza swoops in to win Fermina Daza over. Throughout the book, characters mistake symptoms of love for symptoms of cholera; and lovers block out the world by claiming to have cholera and self-quarantining.

As a thermodynamicist, I see the second law of thermodynamics in every chapter. The second law implies that time marches only forward, order decays, and randomness scatters information to the wind. García Márquez depicts his characters aging, aging more, and aging more. Many characters die. Florentino Ariza’s mother loses her memory to dementia or Alzheimer’s disease. A pawnbroker, she buys jewels from the elite whose fortunes have eroded. Forgetting the jewels’ value one day, she mistakes them for candies and distributes them to children.

The second law bites most, to me, in the doctor’s final words, “Only God knows how much I loved you.” Later, the widow Fermina Daza sighs, “It is incredible how one can be happy for so many years in the midst of so many squabbles, so many problems, damn it, and not really know if it was love or not.” She doesn’t know how much her husband loved her, especially in light of the betrayal that rocked the couple and a rumor of another betrayal. Her husband could have affirmed his love with his dying breath, but he refused: He might have loved her with all his heart, and he might not have loved her; he kept the truth a secret to all but God. No one can retrieve the information after he dies.2

Love in the Time of Cholera—and thermodynamics—must sound like a mouthful of horseradish. But each offers nourishment, an appetizer and an entrée. According to the first law of thermodynamics, the amount of energy in every closed, isolated system remains constant: Physics preserves something. Florentino Ariza preserves his love for decades, despite Fermina Daza’s marrying another man, despite her aging.

The latter preservation can last only so long in the story: Florentino Ariza, being mortal, will die. He claims that his love will last “forever,” but he won’t last forever. At the end of the novel, he sails between two harbors—back and forth, back and forth—refusing to finish crossing a River Styx. I see this sailing as prethermalization: A few quantum systems resist thermalizing, or flowing to the physics analogue of death, for a while. But they succumb later. Florentino Ariza can’t evade the far bank forever, just as the second law of thermodynamics forbids his boat from functioning as a perpetuum mobile.

Though mortal within his story, Florentino Ariza survives as a book character. The book survives. García Márquez wrote about a country I’d never visited, and an era decades before my birth, 33 years before I checked his book out of the library. But the book dazzled me. It pulsed with the vibrancy, color, emotion, and intellect—with the fullness—of life. The book gained another life when the coronavius hit. Thermodynamics dictates that people age and die, but the laws of thermodynamics remain.3 I hope and trust—with the caveat about humanity’s not destroying itself—that Love in the Time of Cholera will pulse in 350 years.

What’s not to love?

1Yes, Caltech has an English library. I found gems in it, and the librarians ordered more when I inquired about books they didn’t have. I commend it to everyone who has access.

2I googled “Only God knows how much I loved you” and was startled to see the line depicted as a hallmark of romance. Please tell your romantic partners how much you love them; don’t make them guess till the ends of their lives.

3Lee Smolin has proposed that the laws of physics change. If they do, the change seems to have to obey metalaws that remain constant.