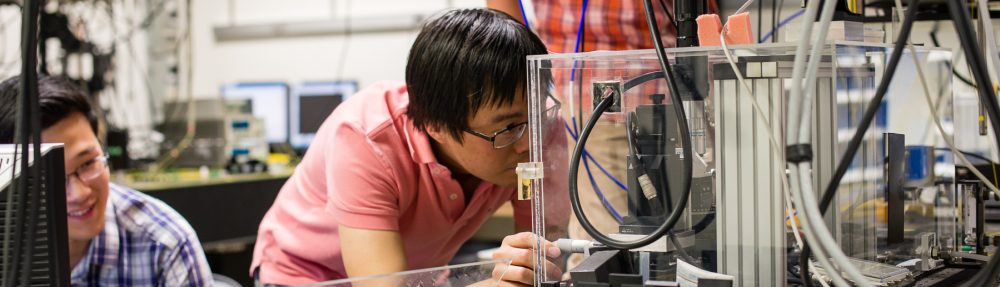

Sara Imari Walker studies ants. Her entomologist colleague Gabriele Valentini cultivates ant swarms. Gabriele coaxes a swarm from its nest, hides the nest, and offers two alternative nests. Gabriele observe the ants’ responses, then analyzes their data with Sara.

Sara doesn’t usually study ants. She trained in physics, information theory, and astrobiology. (Astrobiology is the study of life; life’s origins; and conditions amenable to life, on Earth and anywhere else life may exist.) Sara analyzes how information reaches, propagates through, and manifests in the swarm.

Some ants inspect one nest; some, the other. Few ants encounter both choices. Yet most of the ants choose simultaneously. (How does Gabriele know when an ant chooses? Decided ants carry other ants toward the chosen nest. Undecided ants don’t.)

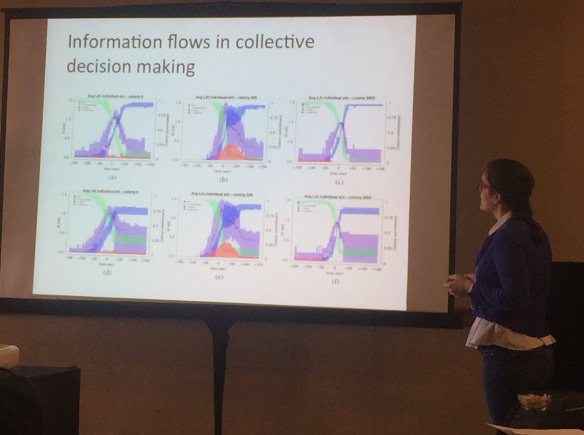

Gabriele and Sara plotted each ant’s status (decided or undecided) at each instant. All the ants’ lines start in the “undecided” region, high up in the graph. Most lines drop to the “decided” region together. Physicists call such dramatic, large-scale changes in many-particle systems “phase transitions.” The swarm transitions from the “undecided” phase to the “decided,” as moisture transitions from vapor to downpour.

Sara versus the ants

Look from afar, and you’ll see evidence of a hive mind: The lines clump and slump together. Look more closely, and you’ll find lags between ants’ decisions. Gabriele and Sara grouped the ants according to their behaviors. Sara explained the grouping at a workshop this spring.

The green lines, she said, are undecided ants.

My stomach dropped like Gabriele and Sara’s ant lines.

People call data “cold” and “hard.” Critics lambast scientists for not appealing to emotions. Politicians weave anecdotes into their numbers, to convince audiences to care.

But when Sara spoke, I looked at her green lines and thought, “That’s me.”

I’ve blogged about my indecisiveness. Postdoc Ning Bao and I formulated a quantum voting scheme in which voters can superpose—form quantum combinations of—options. Usually, when John Preskill polls our research group, I abstain from voting. Politics, and questions like “Does building a quantum computer require only engineering or also science?”,1 have many facets. I want to view such questions from many angles, to pace around the questions as around a sculpture, to hear other onlookers, to test my impressions on them, and to cogitate before choosing.2 However many perspectives I’ve gathered, I’m missing others worth seeing. I commiserated with the green-line ants.

I first met Sara in the building behind the statue. Sara earned her PhD in Dartmouth College’s physics department, with Professor Marcelo Gleiser.

Sara presented about ants at a workshop hosted by the Beyond Center for Fundamental Concepts in Science at Arizona State University (ASU). The organizers, Paul Davies of Beyond and Andrew Briggs of Oxford, entitled the workshop “The Power of Information.” Participants represented information theory, thermodynamics and statistical mechanics, biology, and philosophy.

Paul and Andrew posed questions to guide us: What status does information have? Is information “a real thing” “out there in the world”? Or is information only a mental construct? What roles can information play in causation?

We paced around these questions as around a Chinese viewing stone. We sat on a bench in front of those questions, stared, debated, and cogitated. We taught each other about ants, artificial atoms, nanoscale machines, and models for information processing.

Chinese viewing stone in Yuyuan Garden in Shanghai

I wonder if I’ll acquire opinions about Paul and Andrew’s questions. Maybe I’ll meander from “undecided” to “decided” over a career. Maybe I’ll phase-transition like Sara’s ants. Maybe I’ll remain near the top of her diagram, a green holdout.

I know little about information’s power. But Sara’s plot revealed one power of information: Information can move us—from homeless to belonging, from ambivalent to decided, from a plot’s top to its bottom, from passive listener to finding yourself in a green curve.

With thanks to Sara Imari Walker, Paul Davies, Andrew Briggs, Katherine Smith, and the Beyond Center for their hospitality and thoughts.

1By “only engineering,” I mean not “merely engineering” pejoratively, but “engineering and no other discipline.”

2I feel compelled to perform these activities before choosing. I try to. Psychological experiments, however, suggest that I might decide before realizing that I’ve decided.