You can’t escape him, working where information theory meets statistical mechanics.

Information theory concerns how efficiently we can encode information, compute, evade eavesdroppers, and communicate. Statistical mechanics is the physics of many particles. We can’t track every particle in a material, such as a sheet of glass. Instead, we reason about how the conglomerate likely behaves. Since we can’t know how all the particles behave, uncertainty blunts our predictions. Uncertainty underlies also information theory: You can think that your brother wished you a happy birthday on the phone. But noise corroded the signal; he might have wished you a madcap Earth Day.

Edwin Thompson Jaynes united the fields, in two 1957 papers entitled “Information theory and statistical mechanics.” I’ve cited the papers in at least two of mine. Those 1957 papers, and Jaynes’s philosophy, permeate pockets of quantum information theory, statistical mechanics, and biophysics. Say you know a little about some system, Jaynes wrote, like a gas’s average energy. Say you want to describe the gas’s state mathematically. Which state can you most reasonably ascribe to the gas? The state that, upon satisfying the average-energy constraint, reflects our ignorance of the rest of the gas’s properties. Information theorists quantify ignorance with a function called entropy, so we ascribe to the gas a large-entropy state. Jaynes’s Principle of Maximum Entropy has spread from statistical mechanics to image processing and computer science and beyond. You can’t evade Ed Jaynes.

I decided to turn the tables on him this December. I was visiting to Washington University in St. Louis, where Jaynes worked until six years before his 1998 death. Haunted by Jaynes, I’d hunt down his ghost.

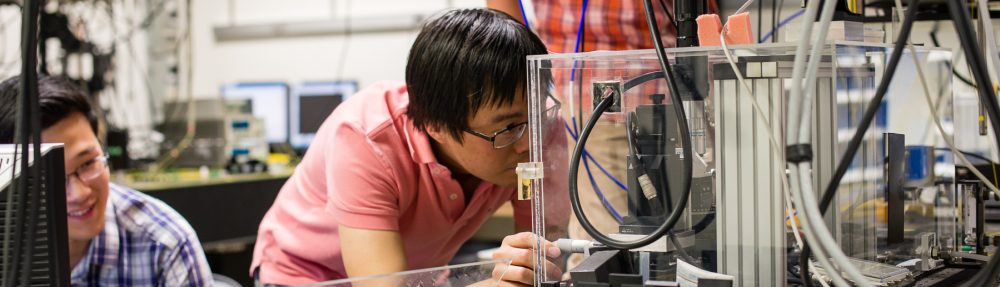

I began with my host, Kater Murch. Kater’s lab performs experiments with superconducting qubits. These quantum circuits sustain currents that can flow forever, without dissipating. I questioned Kater over hummus, the evening after I presented a seminar about quantum uncertainty and equilibration. Kater had arrived at WashU a decade-and-a-half after Jaynes’s passing but had kept his ears open.

Ed Jaynes, Kater said, consulted for a startup, decades ago. The company lacked the funds to pay him, so it offered him stock. That company was Varian, and Jaynes wound up with a pretty penny. He bought a mansion, across the street from campus, where he hosted the physics faculty and grad students every Friday. He’d play a grand piano, and guests would accompany him on instruments they’d bring. The department doubled as his family.

The library kept a binder of Jaynes’s papers, which Kater had skimmed the previous year. What clarity shined through those papers! With a touch of pride, Kater added that he inhabited Jaynes’s former office. Or the office next door. He wasn’t certain.

I passed the hummus to a grad student of Kater’s. Do you hear stories about Jaynes around the department? I asked. I’d heard plenty about Feynman, as a PhD student at Caltech.

Not many, he answered. Just in conversations like this.

Later that evening, I exchanged emails with Kater. A contemporary of Jaynes’s had attended my seminar, he mentioned. Pity that I’d missed meeting the contemporary.

The following afternoon, I climbed to the physics library on the third floor of Crow Hall. Portraits of suited men greeted me. At the circulation desk, I asked for the binders of Jaynes’s papers.

Who? asked the student behind the granola bars advertised as “Free study snacks—help yourself!”

E.T. Jaynes, I repeated. He worked here as a faculty member.

She turned to her computer. Can you spell that?

I obeyed while typing the name into the computer for patrons. The catalogue proffered several entries, one of which resembled my target. I wrote down the call number, then glanced at the notes over which the student was bending: “The harmonic oscillator.” An undergrad studying physics, I surmised. Maybe she’ll encounter Jaynes in a couple of years.

I hiked upstairs, located the statistical-mechanics section, and ran a finger along the shelf. Hurt and Hermann, Itzykson and Drouffe, …Kadanoff and Baym. No Jaynes? I double-checked. No Jaynes.

Upon descending the stairs, I queried the student at the circulation desk. She checked the catalogue entry, then ahhhed. You’d have go to the main campus library for this, she said. Do you want directions? I declined, thanked her, and prepared to return to Kater’s lab. Calculations awaited me there; I’d have no time for the main library.

As I reached the physics library’s door, a placard caught my eye. It appeared to list the men whose portraits lined the walls. Arthur Compton…I only glanced at the placard, but I didn’t notice any “Jaynes.”

Arthur Compton greeted me also from an engraving en route to Kater’s lab. Down the hall lay a narrow staircase on whose installation, according to Kater, Jaynes had insisted. Physicists would have, in the stairs’ absence, had to trek down the hall to access the third floor. Of course I wouldn’t photograph the staircase for a blog post. I might belong to the millenial generation, but I aim and click only with purpose. What, though, could I report in a blog post?

That night, I googled “e.t. jaynes.” His Wikipedia page contained only introductory and “Notes” sections. A WashU website offered a biography and unpublished works. But another tidbit I’d heard in the department yielded no Google hits, at first glance. I forbore a second glance, navigated to my inbox, and emailed Kater about plans for the next day.

I’d almost given up on Jaynes when Kater responded. After agreeing to my suggestion, he reported feedback about my seminar: A fellow faculty member “thought that Ed Jaynes (his contemporary) would have been very pleased.”

The email landed in my “Nice messages” folder within two shakes.

Leaning back, I reevaluated my data about Jaynes. I’d unearthed little, and little surprise: According to the WashU website, Jaynes “would undoubtedly be uncomfortable with all of the attention being lavished on him now that he is dead.” I appreciate privacy and modesty. Nor does Jaynes need portraits or engravings. His legacy lives in ideas, in people. Faculty from across his department attended a seminar about equilibration and about how much we can know about quantum systems. Kater might or might not inhabit Jaynes’s office. But Kater wears a strip cut from Jaynes’s mantle: Kater’s lab probes the intersection of information theory and statistical mechanics. They’ve built a Maxwell demon, a device that uses information as a sort of fuel to perform thermodynamic work.

I’ve blogged about legacies that last. Assyrian reliefs carved in alabaster survive for millennia, as do ideas. Jaynes’s ideas thrive; they live even in me.

Did I find Ed Jaynes’s ghost at WashU? I think I honored it, by pursuing calculations instead of pursuing his ghost further. I can’t say whether I found his ghost. But I gained enough information.

With thanks to Kater and to the Washington University Department of Physics for their hospitality.