Shortly after becoming a Fellow of QuICS, the Joint Center for Quantum Information and Computer Science, I received an email from a university communications office. The office wanted to take professional photos of my students and postdocs and me. You’ve probably seen similar photos, in which theoretical physicists are writing equations, pointing at whiteboards, and thinking deep thoughts. No surprise there.

A big surprise followed: Tom Ventsias, the director of communications at the University of Maryland Institute for Advanced Computer Studies (UMIACS), added, “I wanted to hear your thoughts about possibly doing a dual photo shoot for you—one more ‘traditional,’ one ‘quantum steampunk’ style.”

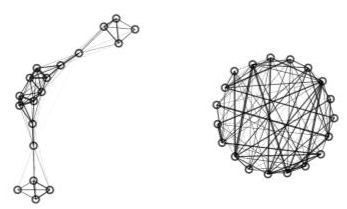

Steampunk, as Quantum Frontiers regulars know, is a genre of science fiction. It combines futuristic technologies, such as time machines and automata, with Victorian settings. I call my research “quantum steampunk,” as it combines the cutting-edge technology of quantum information science with the thermodynamics—the science of energy—developed during the 1800s. I’ve written a thesis called “Quantum steampunk”; authored a trade nonfiction book with the same title; and presented enough talks about quantum steampunk that, strung together, they’d give one laryngitis. But I don’t own goggles, hoop skirts, or petticoats. The most steampunk garb I’d ever donned before this autumn, I wore for a few minutes at age six or so, for dress-up photos at a theme park. I don’t even like costumes.

But I earned my PhD under the auspices of fellow Quantum Frontiers blogger John Preskill,1 whose career suggests a principle to live by: While unravelling the universe’s nature and helping to shape humanity’s intellectual future, you mustn’t take yourself too seriously. This blog has exhibited a photo of John sitting in Caltech’s information-sciences building, exuding all the gravitas of a Princeton degree, a Harvard degree, and world-impacting career—sporting a baseball glove you’d find in a high-school gym class, as though it were a Tag Heuer watch. John adores baseball, and the photographer who documented Caltech’s Institute for Quantum Information and Matter brought out the touch of whimsy like the ghost of a smile.

Let’s try it, I told Tom.

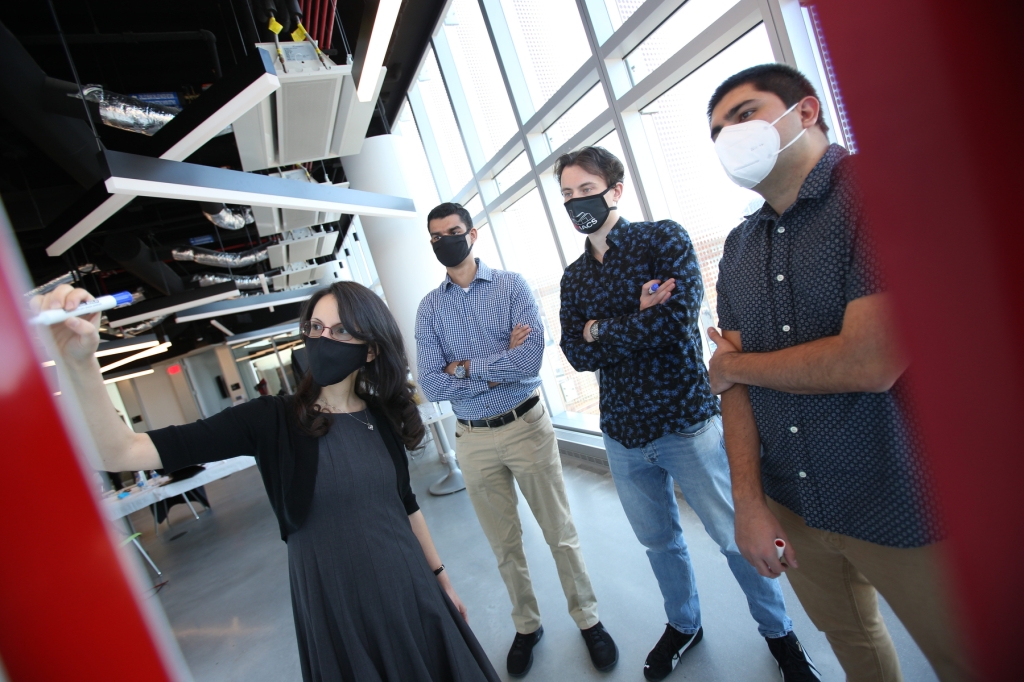

One rust-colored November afternoon, I climbed to the top of UMIACS headquarters—the Iribe Center—whose panoramic view of campus begs for photographs. Two students were talking in front of a whiteboard, and others were lunching on the sandwiches, fruit salad, and cheesecake ordered by Tom’s team. We took turns brandishing markers, gesturing meaningfully, and looking contemplative.

Then, the rest of my team dispersed, and the clock rewound 150 years.

The professionalism and creativity of Tom’s team impressed me. First, they’d purchased a steampunk hat, complete with goggles and silver wires. Recalling the baseball-glove photo, I suggested that I wear the hat while sitting at a table, writing calculations as I ordinarily would.

Then, the team upped the stakes. Earlier that week, Maria Herd, a member of the communications office, had driven me to the University of Maryland performing-arts center. We’d sifted through the costume repository until finding skirts, vests, and a poofy white shirt reminiscent of the 1800s. I swapped clothes near the photo-shoot area, while the communications team beamed a London street in from the past. Not really, but they nearly did: They’d found a backdrop suitable for the 2020 Victorian-era Netflix hit Enola Holmes and projected the backdrop onto a screen. I stood in front of the screen, and a sheet of glass stood in front of me. I wrote equations on the glass while the photographer, John Consoli, snapped away.

The final setup, I would never have dreamed of. Days earlier, the communications team had located an elevator lined, inside, with metal links. They’d brought colorful, neon-lit rods into the elevator and experimented with creating futuristic backdrops. On photo-shoot day, they positioned me in the back of the elevator and held the light-saber-like rods up.

But we couldn’t stop anyone from calling the elevator. We’d ride up to the third or fourth floor, and the door would open. A student would begin to step in; halt; and stare my floor-length skirt, the neon lights, and the photographer’s back.

“Feel free to get in.” John’s assistant, Gail Marie Rupert, would wave them inside. The student would shuffle inside—in most cases—and the door would close.

“What floor?” John would ask.

“Um…one.”

John would twist around, press the appropriate button, and then turn back to his camera.

Once, when the door opened, the woman who entered complimented me on my outfit. Another time, the student asked if he was really in the Iribe Center. I regard that question as evidence of success.

John Consoli took 654 photos. I found the process fascinating, as a physicist. I have a domain of expertise; and I know the feeling of searching for—working toward—pushing for—a theorem or a conceptual understanding that satisfies me, in that domain. John’s area of expertise differs from mine, so I couldn’t say what he was searching for. But I recognized his intent and concentration, as Gail warned him that time had run out and he then made an irritated noise, inched sideways, and stole a few more snapshots. I felt like I was seeing myself in a reflection—not in the glass I was writing on, but in another sphere of the creative life.

The communications team’s eagerness to engage in quantum steampunk—to experiment with it, to introduce it into photography, to make it their own—bowled me over. Quantum steampunk isn’t just a stack of papers by one research group; it’s a movement. Seeing a team invest its time, energy, and imagination in that movement felt like receiving a deep bow or curtsy. Thanks to the UMIACS communications office for bringing quantum steampunk to life.

1Who hasn’t blogged in a while. How about it, John?