What’s it like to publish a book?

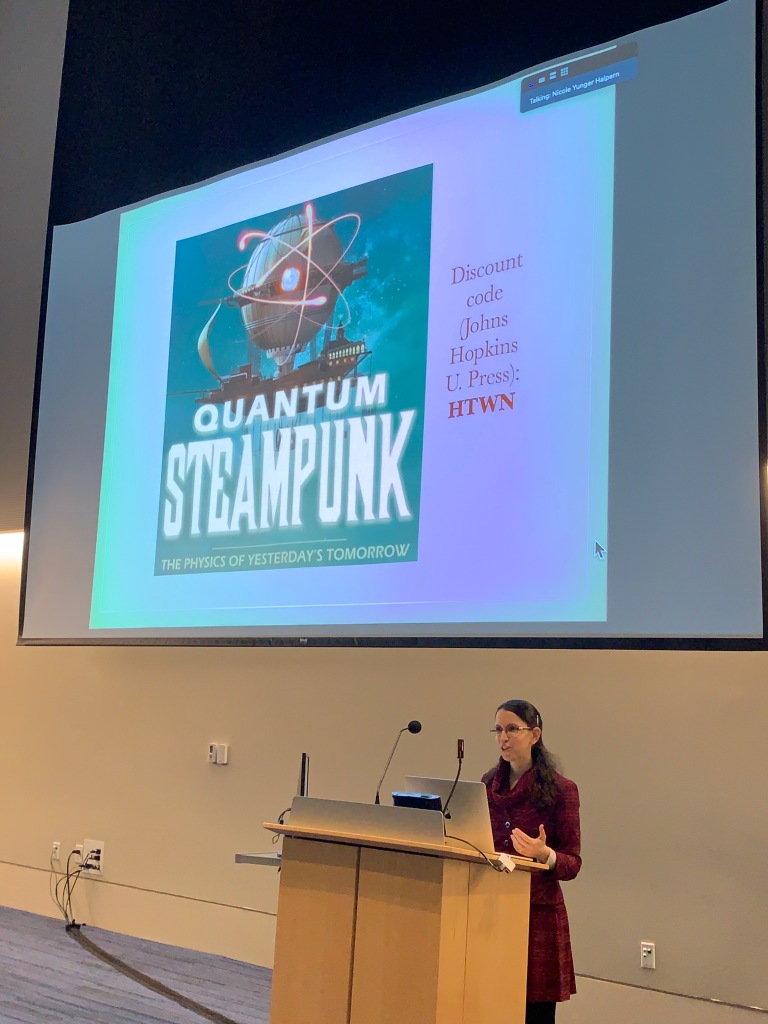

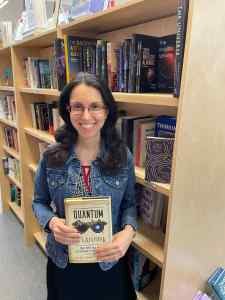

I’ve faced the question again and again this year, as my book Quantum Steampunk hit bookshelves in April. Two responses suggest themselves.

On the one hand, I channel the Beatles: It’s a hard day’s night. Throughout the publication process, I undertook physics research full-time. Media opportunities squeezed themselves into the corners of the week: podcast and radio-show recordings, public-lecture preparations, and interviews with journalists. After submitting physics papers to coauthors and journals, I drafted articles for Quanta Magazine, Literary Hub, the New Scientist newsletter, and other venues—then edited the articles, then edited them again, and then edited them again. Often, I apologized to editors about not having the freedom to respond to their comments till the weekend. Before public-lecture season hit, I catalogued all the questions that I imagined anyone might ask, and I drafted answers. The resulting document spans 16 pages, and I study it before every public lecture and interview.

Answer number two: Publishing a book is like a cocktail of watching the sun rise over the Pacific from Mt. Fuji, taking off in an airplane for the first time, and conducting a symphony in Carnegie Hall.1 I can scarcely believe that I spoke in the Talks at Google lecture series—a series that’s hosted Tina Fey, Noam Chomsky, and Andy Weir! And I found my book mentioned in the Boston Globe! And in a Dutch science publication! If I were an automaton from a steampunk novel, the publication process would have wound me up for months.

Publishing a book has furnished my curiosity cabinet of memories with many a seashell, mineral, fossil, and stuffed crocodile. Since you’ve asked, I’ll share eight additions that stand out.

1) I guest-starred on a standup-comedy podcast. Upon moving into college, I received a poster entitled 101 Things to Do Before You Graduate from Dartmouth. My list of 101 Things I Never Expected to Do in a Physics Career include standup comedy.2 I stand corrected.

Comedian Anthony Jeannot bills his podcast Highbrow Drivel as consisting of “hilarious conversations with serious experts.” I joined him and guest comedienne Isabelle Farah in a discussion about film studies, lunch containers, and hippies, as well as quantum physics. Anthony expected me to act as the straight man, to my relief. That said, after my explanation of how quantum computers might help us improve fertilizer production and reduce global energy consumption, Anthony commented that, if I’d been holding a mic, I should have dropped it. I cherish the memory despite having had to look up the term mic drop when the recording ended.

2) I met Queen Victoria. In mid-May, I arrived in Canada to present about my science and my book at the University of Toronto. En route to the physics department, I stumbled across the Legislative Assembly of Ontario. Her Majesty was enthroned in front of the intricate sandstone building constructed during her reign. She didn’t acknowledge me, of course. But I hope she would have approved of the public lecture I presented about physics that blossomed during her era.

3) You sent me your photos of Quantum Steampunk. They arrived through email, Facebook, Twitter, text, and LinkedIn. They showed you reading the book, your pets nosing it, steampunk artwork that you’d collected, and your desktops and kitchen counters. The photographs have tickled and surprised me, although I should have expected them, upon reflection: Quantum systems submit easily to observation by their surroundings.3 Furthermore, people say that art—under which I classify writing—fosters human connection. Little wonder, then, that quantum physics and writing intersect in shared book selfies.

4) A great-grandson of Ludwig Boltzmann’s emailed. Boltzmann, a 19th-century Austrian physicist, helped mold thermodynamics and its partner discipline statistical mechanics. So I sat up straighter upon opening an email from a physicist descended from the giant. Said descendant turned out to have watched a webinar I’d presented for the magazine Physics Today. Although time machines remain in the domain of steampunk fiction, they felt closer to reality that day.

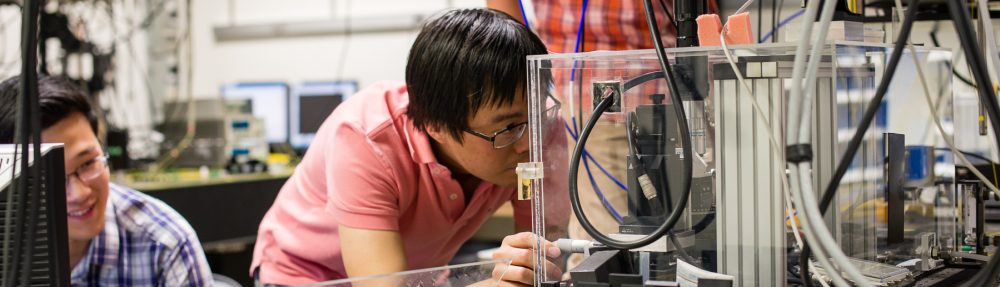

5) An experiment bore out a research goal inspired by the book. My editors and I entitled the book’s epilogue Where to next? The future of quantum steampunk. The epilogue spurred me to brainstorm about opportunities and desiderata—literally, things desired. Where did I want for quantum thermodynamics to head? I shared my brainstorming with an experimentalist later that year. We hatched a project, whose experiment concluded this month. I’ll leave the story for after the paper debuts, but I can say for now that the project gives me chills—in a good way.

6) I recited part of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” with a fellow physicist at a public lecture. The Harvard Science Book Talks form a lecture series produced by the eponymous university and bookstore. I presented a talk hosted by Jacob Barandes—a Harvard physics lecturer, the secret sauce behind the department’s graduate program, and an all-around exemplar of erudition. He asked how entropy relates to “The Raven.”

For the full answer, see chapter 11 of my book. Briefly: Many entropies exist. They quantify the best efficiencies with which we can perform thermodynamic tasks such as running an engine. Different entropies can quantify different tasks’ efficiencies if the systems are quantum, otherwise small, or far from equilibrium—outside the purview of conventional 19th-century thermodynamics. Conventional thermodynamics describes many-particle systems, such as factory-scale steam engines. We can quantify conventional systems’ efficiencies using just one entropy: the thermodynamic entropy that you’ve probably encountered in connection with time’s arrow. How does this conventional entropy relate to the many quantum entropies? Imagine starting with a quantum system, then duplicating it again and again, until accruing infinitely many copies. The copies’ quantum entropies converge (loosely speaking), collapsing onto one conventional-looking entropy. The book likens this collapse to a collapse described in “The Raven”:

The speaker is a young man who’s startled, late one night, by a tapping sound. The tapping exacerbates his nerves, which are on edge due to the death of his love: “Deep into that darkness peering, long I stood there wondering, fearing, / Doubting, dreaming dreams no mortal ever dared to dream before.” The speaker realizes that the tapping comes from the window, whose shutter he throws open. His wonders, fears, doubts, and dreams collapse onto a bird’s form as a raven steps inside. So do the many entropies collapse onto one entropy as the system under consideration grows infinitely large. We could say, instead, that the entropies come to equal each other, but I’d rather picture “The Raven.”

I’d memorized the poem in high school but never had an opportunity to recite it for anyone—and it’s a gem to declaim. So I couldn’t help reciting a few stanzas in response to Jacob. But he turned out to have memorized the poem, too, and responded with the next several lines! Even as a physicist, I rarely have the chance to reach such a pinnacle of nerdiness.

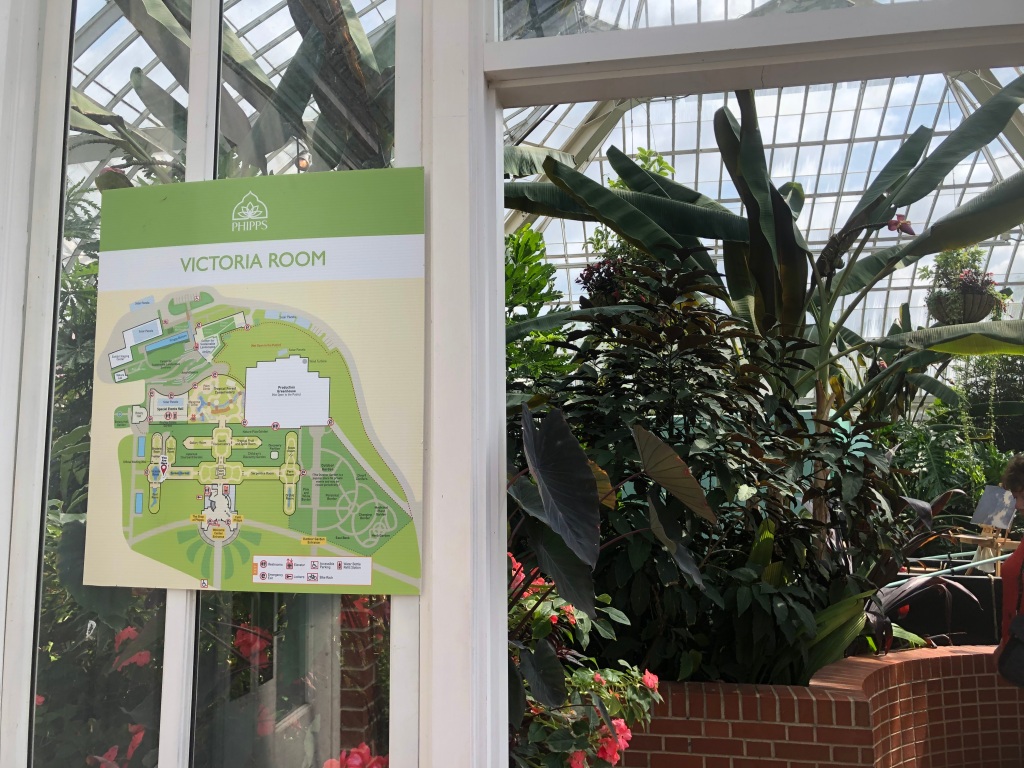

7) I stumbled across a steam-driven train in Pittsburgh. Even before self-driving cars heightened the city’s futuristic vibe, Pittsburgh has been as steampunk as the Nautilus. Captains of industry (or robber barons, if you prefer) raised the city on steel that fed the Industrial Revolution.4 And no steampunk city would deserve the title without a Victorian botanical garden.

A Victorian botanical garden features in chapter 5 of my book. To see a real-life counterpart, visit the Phipps Conservatory. A poem in glass and aluminum, the Phipps opened in 1893 and even boasts a Victoria Room.

I sneaked into the Phipps during the Pittsburgh Quantum Institute’s annual conference, where I was to present a public lecture about quantum steampunk. Upon reaching the sunken garden, I stopped in my tracks. Yards away stood a coal-black, 19th-century steam train.

At least, an imitation train stood yards away. The conservatory had incorporated Monet paintings into its scenery during a temporary exhibition. Amongst the palms and ponds were arranged props inspired by the paintings. Monet painted The Gare Saint-Lazare: Arrival of a Train near a station, so a miniature train stood behind a copy of the artwork. The scene found its way into my public lecture—justifying my playing hooky from the conference for a couple of hours (I was doing research for my talk!).

My book’s botanical garden houses hummingbirds, wildebeests, and an artificial creature called a Yorkicockasheepapoo. I can’t promise that you’ll spy Yorkicockasheepapoos while wandering the Phipps, but send me a photo if you do.

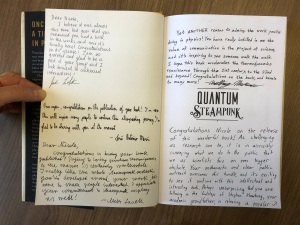

8) My students and postdocs presented me with a copy of Quantum Steampunk that they’d signed. They surprised me one afternoon, shortly after publication day, as I was leaving my office. The gesture ranks as one of the most adorable things that’ve ever happened to me, and their book is now the copy that I keep on campus.

Students…book-selfie photographers…readers halfway across the globe who drop a line…People have populated my curiosity cabinet of with some of the most extraordinary book-publication memories. Thanks for reading, and thanks for sharing.

1Or so I imagine, never having watched the sun rise from Mt. Fuji or conducted any symphony, let alone one at Carnegie Hall, and having taken off in a plane for the first time while two months old.

2Other items include serve as an extra in a film, become stranded in Taiwan, and publish a PhD thesis whose title contains the word “steampunk.”

3This ease underlies the difficulty of quantum computing: Any stray particle near a quantum computer can “observe” the computer—interact with the computer and carry off a little of the information that the computer is supposed to store.

4The Pittsburgh Quantum Institute includes Carnegie Mellon University, which owes its name partially to captain of industry Andrew Carnegie.