“Fractons” is my favorite new toy (short for quantum many-body toy models). It has amazing functions that my old toys do not have; it is so new that there are tons of questions waiting to be addressed; it is perfectly situated at the interface between quantum information and condensed matter and has attracted a lot of interest and efforts from both sides; and it gives me excuses and new incentives to learn more math. I have been having a lot of fun playing with it in the last couple years and in the process, I had the great opportunity to work with some amazing collaborators: Han Ma and Mike Hermele at Boulder, Ethan Lake at MIT, Wilbur Shirley at Caltech, Kevin Slagle at U Toronto and Zhenghan Wang at Station Q. Together we have written a few papers on this subject, but I always felt there are more interesting stories and more excitement in me than what can be properly contained in scientific papers. Hence this blog post.

How I first learned about Fractons

Back in the early 2000s, a question that kept attracting and frustrating people in quantum information is how to build a quantum hard drive to store quantum information. This is of course a natural question to ask as quantum computing has been demonstrated to be possible, at least in theory, and experimental progress has shown great potential. It turned out, however, that the question is one of those deceptively enticing ones which are super easy to state, but extremely hard to answer. In a classical hard drive, information is stored using magnetism. Quantum information, instead of being just 0 and 1, is represented using superpositions of 0 and 1, and can be probed in non-commutative ways (that is, measuring along different directions can alter previous answers). To store quantum information, we need “magnetism” in all such non-commutative channels. But how can we do that?

At that time, some proposals had been made, but they either involve actively looking for and correcting errors throughout the time during which information is stored (which is something we never have to do with our classical hard drives) or going into four spatial dimensions. Reliable passive storage of quantum information seemed out of reach in the three-dimensional world we live in, even at the level of a proof of principle toy model!

Given all the previously failed attempts and without a clue about where else to look, this problem probably looked like a dead-end to many. But not to Jeongwan Haah, a fearless graduate student in Preskill’s group at IQIM at that time, who turned the problem from guesswork into a systematic computer search (over a constrained set of models). The result of the search surprised everyone. Jeongwan found a three-dimensional quantum spin model with physical properties that had never been seen before, making it a better quantum hard drive than any other model that we know of!

The model looks surprising not only to the quantum information community, but even more so to the condensed matter community. It is a strongly interacting quantum many-body model, a subject that has been under intense study in condensed matter physics. Yet it exhibits some very strange behaviors whose existence had not even been suspected. It is a condensed matter discovery made not from real materials in real experiments, but through computer search!

Excitations (stars) in Haah’s code live at the corner of a fractal.

In condensed matter systems, what we know can happen is that elementary excitations can come in the form of point particles – usually called quasi-particles – which can then move around and interact with other excitations. In Jeongwan’s model, now commonly referred to as Haah’s code, elementary excitations still come in the form of point particles, but they cannot freely move around. Instead, if they want to move, four of them have to coordinate with each other to move together, so that they stay at the vertices of a fractal shaped structure! The restricted motion of the quasi-particles leads to slower dynamics at low energy, making the model much better suited for the purpose of storing quantum information.

But how can something like this happen? This is the question that I want to yell out loud every time I read Jeongwan’s papers or listen to his talks. Leaving aside the motivation of building a quantum hard drive, this model presents a grand challenge to the theoretical framework we now have in condensed matter. All of our intuitions break down in predicting the behavior of this model; even some of the most basic assumptions and definitions do not apply.

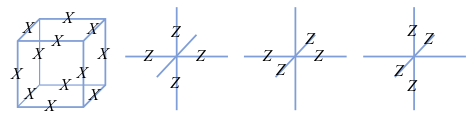

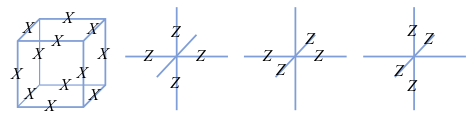

The interactions in Haah’s code involve eight spins at a time (the eight Z’s and eight X’s in each cube).

I felt so uncomfortable and so excited at the same time because there was something out there that should be related to things I know, yet I totally did not understand how. And there was an even bigger problem. I was like a sick person going to a doctor but unable to pinpoint what was wrong. Something must have been wrong, but I didn’t know what that was and I didn’t know how to even begin to look for it. The model looked so weird. Interaction involved eight spins at a time; there was no obvious symmetry other than translation. Jeongwan, with his magic math power, worked out explicitly many of the amazing properties of the model, but that to me only added to the mystery. Where did all these strange properties coming from?

From the unfathomable to the seemingly approachable

I remained in this superposition of excited state and powerless state for several years, until Jeongwan moved to MIT and posted some papers with Sagar Vijay and Liang Fu in 2015 and 2016.

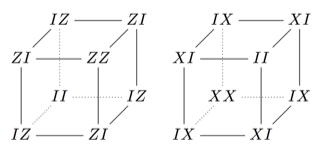

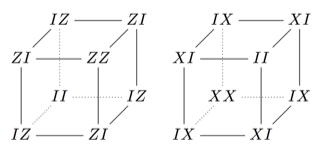

Interaction terms in a nicer looking fracton model.

In these papers, they listed several other models, which, similar to Haah’s code, contain quasi-particle excitations whose motion is constrained. The constraints are weaker and these models do not make good quantum hard drives, but they still represent new condensed matter phenomena. What’s nice about these models is that the form of interaction is more symmetric, takes a simpler form, or is similar to some other models we are familiar with. The quasi-particles do not need a fractal-shaped structure to move around, instead they move along a line, in a plane, or at the corner of a rectangle. In fact, as early as 2005 – six years before Haah’s code, Claudio Chamon at Boston University already proposed a model of this kind. Together with the previous fractal examples, these models are what’s now being referred to as the fracton models. If the original Haah’s code looks like an ET from beyond the milky way, these models at least seem to live somewhere in the solar system. So there must be something that we can do to understand them better!

Obviously, I was not the only one who felt this way. A flurry of papers appeared on these “fracton” models. People came at these models armed with their favorite tools in condensed matter, looking for an entry point to crack them open. The two approaches that I found most attractive was the coupled layer construction and the higher rank gauge theory, and I worked on these ideas together with Han Ma, Ethan Lake and Michael Hermele. Each approach comes from a different perspective and establishes a connection between fractons and physical models that we are familiar with. In the coupled layer construction, the connection is to the 2D discrete gauge theories, while in the higher rank approach it is to the 3D gauge theory of electromagnetism.

I was excited about these results. They each point to simple physical mechanisms underlying the existence of fractons in some particular models. By relating these models to things I already know, I feel a bit relieved. But deep down, I know that this is far from the complete story. Our understanding barely goes beyond the particular models discussed in the paper. In condensed matter, we spend a lot of time studying toy models; but toy models are not the end goal. Toy models are only meaningful if they represent some generic feature in a whole class of models. It is not clear at all to what extent this is the case for fractons.

Step zero: define “order”, define “topological order”

I gave a talk about these results at KITP last fall under the title “Fracton Topological Order”. It was actually too big a title because all we did was to study specific realizations of individual models and analyze their properties. To claim topological order, one needs to show much more. The word “order” refers to the common properties of a continuous range of models within the same phase. For example, crystalline order refers to the regular lattice organization of atoms in the solid phase within a continuous range of temperature and pressure. When the word “topological” is added in front of “order”, it signifies that such properties are usually directly related to the topology of the system. A prototypical example is the fractional quantum Hall system, whose ground state degeneracy is directly determined by the topology of the manifold the system lives in. For fractons, we are far from an understanding at this level. We cannot answer basic questions like what range of models form a phase, what is the order (the common properties of this whole range of models) characterizing each phase, and in what sense is the order topological. So, the title was more about what I hope will happen than what has already happened.

But it did lead to discussions that could make things happen. After my talk, Zhenghan Wang, a mathematician at Microsoft Station Q, said to me, “I would agree these fracton models are topological if you can show me how to define them on different three manifolds”. Of course! How can I claim anything related to topology if all I know is one model on a cubic lattice with periodic boundary condition? It is like claiming a linear relation between two quantities with only one data point.

But how to get more data points? Well, from the paper by Haah, Vijay and Fu, we knew how to define the model on cubic lattices. With periodic boundary conditions, the underlying manifold is a three torus. Is it possible to have a cubic lattice, or something similar, in other three manifolds as well? Usually, this kind of request would be too much to ask. But it turns out that if you whisper your wish to the right mathematician, even the craziest ones can come true. With insightful suggestions from Michael Freedman (the Fields medalist leading Station Q) and Zhenghan, and through the amazing work of Kevin Slagle (U Toronto) and Wilbur Shirley (Caltech), we found that if we make use of a structure called Total Foliation, one of the fracton models can be generalized to different kinds of three manifolds and we can see how the properties of the model are related to certain topological features of the manifold!

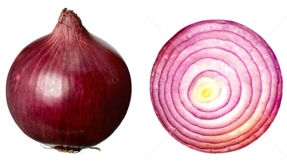

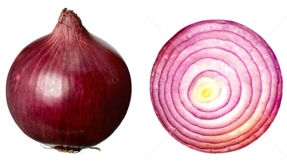

Foliation.

Foliation is the process of dividing a manifold into parallel planes. Total foliation is a set of three foliations which intersect each other in a transversal way. The xy, yz, and zx planes in a cubic lattice form a total foliation and similar constructions can be made for other three manifolds as well.

Things start to get technical from here, but the basic lesson we learned about some of the fracton models is that structural-wise, they pretty much look like an onion. Even though onions look like a three-dimensional object from the outside, they actually grow in a layered structure. Some of the properties of the fracton models are simply determined by the layers, and related

to the topology of the layers. Once we peel off all the layers, we find that for some, there is nothing left while for others, there is a nontrivial core. This observation allows us to better address the previous questions: we defined a fracton phase (one type of it) as models smoothly related to each other after adding or removing layers; the topological nature of the order is manifested in how the properties of the model are determined by the topology of the layers.

to the topology of the layers. Once we peel off all the layers, we find that for some, there is nothing left while for others, there is a nontrivial core. This observation allows us to better address the previous questions: we defined a fracton phase (one type of it) as models smoothly related to each other after adding or removing layers; the topological nature of the order is manifested in how the properties of the model are determined by the topology of the layers.

The onion structure is nice, because it allows us to reduce much of the story from 3D to 2D, where we understand things much better. It clarifies many of the weirdnesses of the fracton model we studied, and there is indication that it may apply to a much wider range of fracton models, so we have an exciting road ahead of us. On the other hand, it is also clear that the onion structure does not cover everything. In particular, it does not cover Haah’s code! Haah’s code cannot be built in a layered way and its properties are in a sense intrinsically three dimensional. So, after finishing this whole journey through the onion field, I will be back to staring at Haah’s code again and wondering what to do with it, like what I have been doing in the eight years since Jeongwan’s paper first came out. But maybe this time I will have some better ideas.

The onion structure is nice, because it allows us to reduce much of the story from 3D to 2D, where we understand things much better. It clarifies many of the weirdnesses of the fracton model we studied, and there is indication that it may apply to a much wider range of fracton models, so we have an exciting road ahead of us. On the other hand, it is also clear that the onion structure does not cover everything. In particular, it does not cover Haah’s code! Haah’s code cannot be built in a layered way and its properties are in a sense intrinsically three dimensional. So, after finishing this whole journey through the onion field, I will be back to staring at Haah’s code again and wondering what to do with it, like what I have been doing in the eight years since Jeongwan’s paper first came out. But maybe this time I will have some better ideas.

to the topology of the layers. Once we peel off all the layers, we find that for some, there is nothing left while for others, there is a nontrivial core. This observation allows us to better address the previous questions: we defined a fracton phase (one type of it) as models smoothly related to each other after adding or removing layers; the topological nature of the order is manifested in how the properties of the model are determined by the topology of the layers.

to the topology of the layers. Once we peel off all the layers, we find that for some, there is nothing left while for others, there is a nontrivial core. This observation allows us to better address the previous questions: we defined a fracton phase (one type of it) as models smoothly related to each other after adding or removing layers; the topological nature of the order is manifested in how the properties of the model are determined by the topology of the layers. The onion structure is nice, because it allows us to reduce much of the story from 3D to 2D, where we understand things much better. It clarifies many of the weirdnesses of the fracton model we studied, and there is indication that it may apply to a much wider range of fracton models, so we have an exciting road ahead of us. On the other hand, it is also clear that the onion structure does not cover everything. In particular, it does not cover Haah’s code! Haah’s code cannot be built in a layered way and its properties are in a sense intrinsically three dimensional. So, after finishing this whole journey through the onion field, I will be back to staring at Haah’s code again and wondering what to do with it, like what I have been doing in the eight years since Jeongwan’s paper first came out. But maybe this time I will have some better ideas.

The onion structure is nice, because it allows us to reduce much of the story from 3D to 2D, where we understand things much better. It clarifies many of the weirdnesses of the fracton model we studied, and there is indication that it may apply to a much wider range of fracton models, so we have an exciting road ahead of us. On the other hand, it is also clear that the onion structure does not cover everything. In particular, it does not cover Haah’s code! Haah’s code cannot be built in a layered way and its properties are in a sense intrinsically three dimensional. So, after finishing this whole journey through the onion field, I will be back to staring at Haah’s code again and wondering what to do with it, like what I have been doing in the eight years since Jeongwan’s paper first came out. But maybe this time I will have some better ideas.