The year I started studying calculus, I took the helm of my high school’s literary magazine. Throughout the next two years, the editorial board flooded campus with poetry—and poetry contests. We papered the halls with flyers, built displays in the library, celebrated National Poetry Month, and jerked students awake at morning assembly (hitherto known as the quiet kid you’d consult if you didn’t understand the homework, I turned out to have a sense of humor and a stage presence suited to quoting from that venerated poet Dr. Seuss.1 Who’d’ve thought?). A record number of contest entries resulted.

That limb of my life atrophied in college. My college—a stereotypical liberal-arts affair complete with red bricks—boasted a literary magazine. But it also boasted English and comparative-literature majors. They didn’t need me, I reasoned. The sun ought to set on my days of engineering creative-writing contests.

I’m delighted to be eating my words, in announcing the Quantum-Steampunk Short-Story Contest.

The Maryland Quantum-Thermodynamics Hub is running the contest this academic year. I’ve argued that quantum thermodynamics—my field of research—resembles the literary and artistic genre of steampunk. Steampunk stories combine Victorian settings and sensibilities with futuristic technologies, such as dirigibles and automata. Quantum technologies are cutting-edge and futuristic, whereas thermodynamics—the study of energy—developed during the 1800s. Inspired by the first steam engines, thermodynamics needs retooling for quantum settings. That retooling is quantum thermodynamics—or, if you’re feeling whimsical (as every physicist should), quantum steampunk.

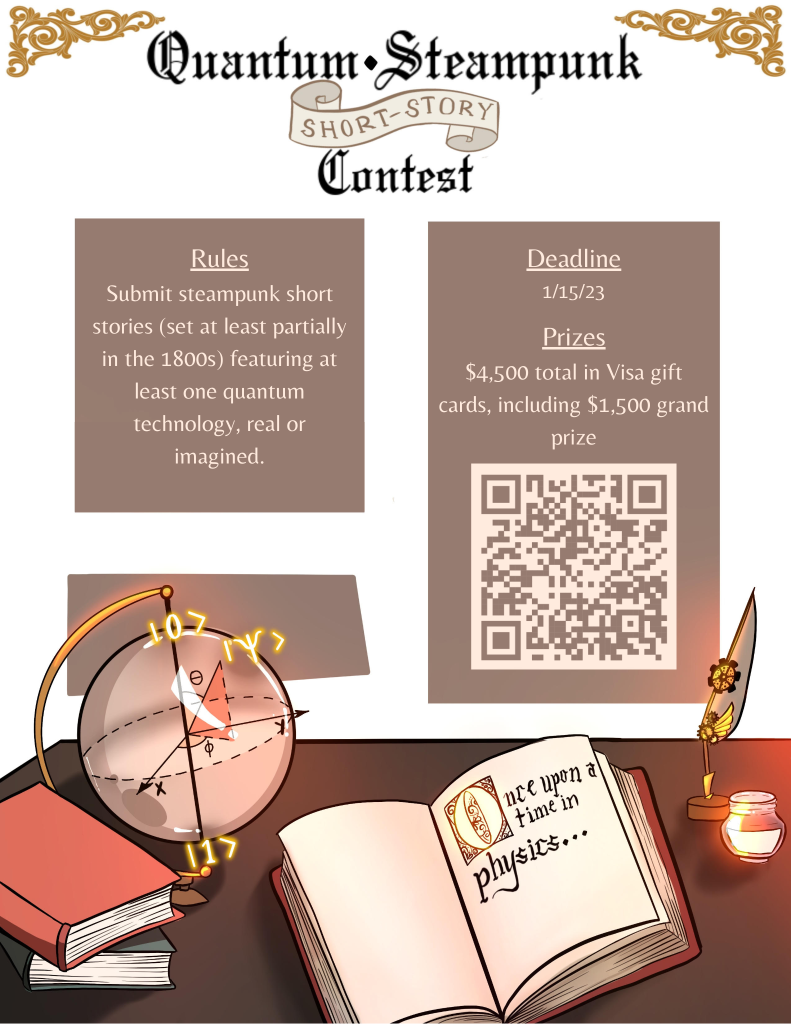

The contest opens this October and closes on January 15, 2023. Everyone aged 13 or over may enter a story, written in English, of up to 3,000 words. Minimal knowledge of quantum theory is required; if you’ve heard of Schrödinger’s cat, superpositions, or quantum uncertainty, you can pull out your typewriter and start punching away.

Entries must satisfy two requirements: First, stories must be written in a steampunk style, including by taking place at least partially during the 1800s. Transport us to Meiji Japan; La Belle Époque in Paris; gritty, smoky Manchester; or a camp of immigrants unfurling a railroad across the American west. Feel free to set your story partially in the future; time machines are welcome.

Second, each entry must feature at least one quantum technology, real or imagined. Real and under-construction quantum technologies include quantum computers, communication networks, cryptographic systems, sensors, thermometers, and clocks. Experimentalists have realized quantum engines, batteries, refrigerators, and teleportation, too. Surprise us with your imagined quantum technologies (and inspire our next research-grant proposals).

In an upgrade from my high-school days, we’ll be awarding $4,500 worth of Visa gift certificates. The grand prize entails $1,500. Entries can also win in categories to be finalized during the judging process; I anticipate labels such as Quantum Technology We’d Most Like to Have, Most Badass Steampunk Hero/ine, Best Student Submission, and People’s Choice Award.

Our judges run the gamut from writers to quantum physicists. Judge Ken Liu‘s latest novel peered out from a window of my local bookstore last month. He’s won Hugo, Nebula, and World Fantasy Awards—the topmost three prizes that pop up if you google “science-fiction awards.” Appropriately for a quantum-steampunk contest, Ken has pioneered the genre of silkpunk, “a technology aesthetic based on a science fictional elaboration of traditions of engineering in East Asia’s classical antiquity.”

Emily Brandchaft Mitchell is an Associate Professor of English at the University of Maryland. She’s authored a novel and published short stories in numerous venues. Louisa Gilder wrote one of the New York Times 100 Notable Books of 2009, The Age of Entanglement. In it, she imagines conversations through which scientists came to understand the core of this year’s Nobel Prize in physics. Jeffrey Bub is a philosopher of physics and a Distinguished University Professor Emeritus at the University of Maryland. He’s also published graphic novels about special relativity and quantum physics with his artist daughter.

Patrick Warfield, a musicologist, serves as the Associate Dean for Arts and Programming at the University of Maryland. (“Programming” as in “activities,” rather than as in “writing code,” the meaning I encounter more often.) Spiros Michalakis is a quantum mathematician and the director of Caltech’s quantum outreach program. You may know him as a scientific consultant for Marvel Comics films.

Walter E. Lawrence III is a theoretical quantum physicist and a Professor Emeritus at Dartmouth College. As department chair, he helped me carve out a niche for myself in physics as an undergrad. Jack Harris, an experimental quantum physicist, holds a professorship at Yale. His office there contains artwork that features dragons.

University of Maryland undergraduate Hannah Kim designed the ad above. She and Jade LeSchack, founder of the university’s Undergraduate Quantum Association, round out the contest’s leadership team. We’re standing by for your submissions through—until the quantum internet exists—the hub’s website. Send us something to dream on.

This contest was made possible through the support of Grant 62422 from the John Templeton Foundation.

1Come to think of it, Seuss helped me prepare for a career in physics. He coined the terms wumbus and nerd; my PhD advisor invented NISQ, the name for a category of quantum devices. NISQ now has its own Wikipedia page, as does nerd.