Hey all, I’m back! I’ve been stuck in a black hole for the past couple years. Nobody ever said that doing a PhD in quantum gravity would be easy. Actually, my advisor John Preskill explicitly warned me that it would be exceptionally difficult (but in an encouraging manner; he was managing my expectations.) I wish I could say that I’ve returned w/ emergent spacetime figured out, but alas, I was simply inspired to write about a heady topic that is quite personal to me: how to increase gender diversity in STEM. (Maybe the key to understanding quantum gravity is to have more women thinking about these questions?)

I’ve been thinking about this topic for well over a decade but my interest bubbled over last week and I decided to write this post. Some entrepreneur friends were on a panel at Caltech (John Hering, Diego Berdakin and Joe Lonsdale) and during a wonderful sub-convo about increasing gender diversity in STEM a male undergrad asked: “as someone who’s only a student, what can I do to help with this issue?” The panel pretty much nailed it with their responses but this is an incredibly important issue and I want to capture some of their comments in writing, to frame this with broader context and to add some personal anecdotes.

Before providing a few recommendations here are some bullets which I think are important in terms of framing this issue.

1. Full stack problem: this isn’t an issue that can be tackled by targeting any specific age range. It especially can’t be tackled by only focusing on recruitment for colleges or STEM jobs. Our current lack of diversity literally starts the day children are born. We have a broad culture of pushing kids away from STEM but these pressures disproportionately target girls.

2. Implicit biases: one of the most damaging and least spoken about mechanisms through which this happens are implicit biases. Very few people understand the depth of this issue and as an extension how guilty WE ALL ARE. Implicit biases are pervasive and they are pushing girls out of STEM. Here are examples from my own childhood which highlight how subtle the issue is.

I have a younger sister who has basically the same brain as myself (truly, we can read each others minds.) I became a theoretical physicist and entrepreneur and she’s a lawyer. This is obviously a worthy profession but how did we choose these paths? For years I’ve been looking back and trying to answer this question. Upon reflection, I was astonished by the strength of my implicit biases.

a. An Uncle helped me build a computer when I was seven. No one did the same for my sister. I spent most of the ages of 7-16 hacking around on computers which provided the foundation for many of the things that I’ve done in my adult life. This gesture by my Uncle was easily one of the most impactful things that anyone has ever done for me.

b. When my sister had computer problems I would treat her like she’s stupid and simply fix the problem for her (these words are overly dramatic but I’m trying to make a point.) Whereas when my male cousin had issues I would sit next to him and patiently explain the underlying issue and teach him how to fix his problem. That teaching a man to fish metaphor is a thing.

c. When people gave us presents they would give me Legos and my sister art supplies or clothes. Gifts didn’t always fall into these categories (obviously) but they almost always had a similar gender-specific split.

d. When I was the first to finish my multiplication tables in 3rd grade, my teacher encouraged me to read science books. When my sister finished she was encouraged to draw. This teacher was female.

e. These are only a few examples of implicit biases. I wasn’t aware of the potential cause-and-effect of my actions while making them. Only after years of reflection and seeing how amplified the problem becomes by making it to the tip of the funnel was I able to connect these personal dots. These biases are so deeply engrained that addressing them requires societal-scale reprogramming — but it starts with enhanced self-awareness. I obviously feel some level of guilt for being oblivious to these actions as a kid. And I’d be delusional to think I’m beyond having similar biases today.

3. Explicit/systematic biases: there’s much broader awareness of these category of biases so I’m mainly going to explain by linking to some recent headlines. The short of it is that on their path to STEM, women have to put up with many more hurdles than men. From hiring biases to sexual harassment. These biases disproportionately adversely affect women. Here’s a tiny sample of some of the most glaring recent headlines:

a. “Geoff Marcy was a serial harasser for at least twenty years” — Gizmodo.

b. “Why women are poor at science, by Harvard president (Larry Summers)” — Guardian headline. Granted, his comments were more nuanced than the media portrayed. But in any case, extremely damaging and evidence of an outmoded way of thinking.

c. “Could it be that researchers find a hiring bias that favors women?” — NPR. I wanted to include this example to highlight that sometimes systematic biases (this isn’t exactly an explicit bias) go the other direction. But of course if we search hard enough we will be able to find specific instances in the stack where the bias favors women. My personal interpretation of this headline is: “the fearless women that have braved decades of doubt may have a minuscule advantage when competing for STEM jobs, but only after they have been disproportionately filtered out of the applicant pool on a massive scale.” Here are some statistics which show why this headline is only scratching the surface: NGCP and Techbridge.

If we acknowledge that this is a problem that literally starts the day children are born, then what can we, as individuals, do about it?

1. Constantly run a mental loop to check your implicit biases. I’m hoping we can compile a list of examples in the comments that can serve as a check-list of things NOT TO DO! E.g. When you ask: “what do you want to be when you grow-up?” Don’t answer before kids can get back to you with something like: “be a princess?” or “be a baseball player?” Those kids might want to be mathematicians! Maryam Mirzakhani or Terry Tao!

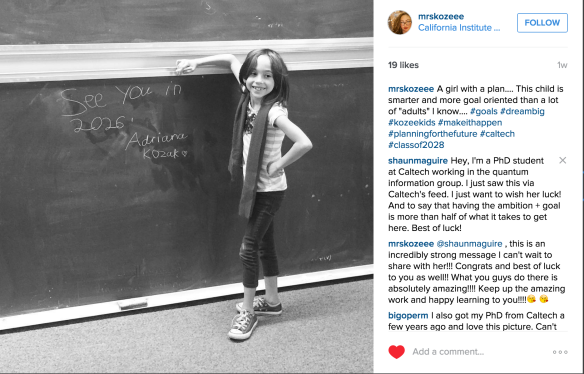

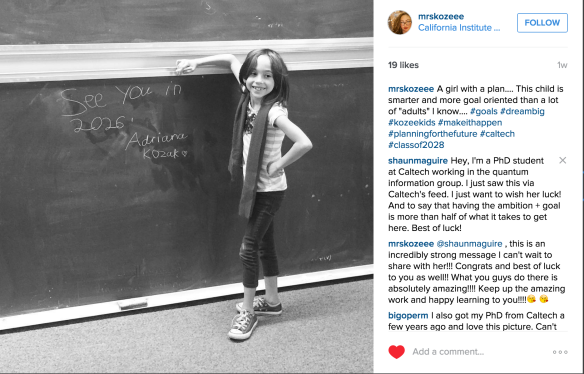

2. Provide encouragement to young girls without being over the top or condescending. Here’s a simple example from the past week. A.K. is ~8 years old and she visited Caltech recently (yes, I got permission from her mother to use this example.) This girl is a rockstar.

The tragic reality is that A.K. is going to spend her next decade being pushed away from STEM. Don’t get me wrong, she’s lucky to have encouraging parents who are preempting this push, but they will be competing with the sway of the media and her peers.

The tragic reality is that A.K. is going to spend her next decade being pushed away from STEM. Don’t get me wrong, she’s lucky to have encouraging parents who are preempting this push, but they will be competing with the sway of the media and her peers.

Small gestures, such as @Caltechedu reposting the above photo on Instagram provides a powerful dosage of motivation. The way I think about it is this: kids, but especially girls, are going to face a persistent push away from STEM. They are going to get teased for being “too smart” + “not girly enough” + “weird” + “nerdy” + etc. Small votes of confidence from people that have made it through and can therefore speak with authority are like little bits of body armor. Comments sting a little bit less when the freedom+success of the other side is visible and you’re being told that you can make it too. Don’t underestimate the power of small gestures. One comment can literally make a world of difference. Do this. But it absolutely must be genuine.

3. Make a conscious effort to share your passion + enthusiasm for STEM. Our culture does an abysmal job of motivating and promoting the beauty + wonder of science. This advice applies to both girls and boys and it’s incredibly important. One of my favorite essays is “A Mathematician’s Lament” by Paul Lockhart. In it he contrasts the way that we teach mathematics compared to how we teach painting and music. Imagine if before letting kids see a finished masterwork or picking up a brush and playing around, we forced them to learn: color theory, the history of art, how to hold a brush, etc! If you’re at Caltech then invite kids to the SURF seminar day or to interesting public lectures. Go give a talk at a local school and explain via examples that science is a work in progress — there’s an infinite amount that we still don’t know! For example, a brilliant non-physicist hacker friend asked me yesterday if the Casimir effect is temperature dependent? The answer is yes, but this is still barely understood theoretically. At what temperature will a gecko’s stick stop working? Questions like this are engaging. It will only take a few hours of your time to emphasize to dozens of kids how exciting science is. Outreach is usually asymmetric.

As an aside, writing this reminded me of an outreach story from 2010. Somehow I finagled travel funds to attend the International Congress of Mathematicians (ICM) in Hyderabad, India. During our day off (one day during a two week conference), I set out early to do some sightseeing and a dude pulled up next to me on a scooter. He asked if I was there for the congress. It’s kind of a long story but after chatting for a bit I agreed to spend the day riding around on his scooter while spreading my passion for mathematics at a variety of schools in the Hyderabad area. I lectured to hundreds of kids that day. I wrote a blog post that ended up getting picked up by a few national newspapers and even made the official ICM newsletter (page six of this; FYI they condensed my post and convoluted some facts.) I’m sure that I ended up benefitting wayyyyyy more from my outreach than any of the students I spoke to. The crazy reality is that outreach is oftentimes like this.

4. There is literally nothing more rewarding than mentoring hyper talented kids and then watching them succeed. This is also incredibly asymmetric. Two hours of your time will provide direction and motivation for months. Do not discount the power of giving kids confidence and a small amount of direction.

In this post, I ignored some very important parts of the problem and also opportunities for addressing it in an attempt to focus on aspects that I think are under appreciated. Specifically how pervasive implicit biases are and how asymmetric outreach is. Increasing diversity in STEM is a societal scale problem that isn’t going to be fixed overnight. However, I believe it’s possible to make huge progress over the next two decades. We’re in the process of taking our first step, which is global-awareness of the problem. And now we need to take the next step which is broad self-awareness about the impacts of our individual actions and implicit biases. It seems to me like wildly increasing our talent pool is a useful endeavor. In the spirit of this blog, unlocking this hidden potential might even be the key to making progress with quantum gravity! And definitely towards making progress on an innumerable number of other science and engineering goals.

And, hey S, sorry for not teaching you more about computers 😦

********************************************************

Now some shameless on-topic plugs to promote my friends:

One of my roommates, Jason Porath, makes Rejected Princesses. This is a great site that all young girls should be aware of. Think badass women meet Disney glorification from a feminist perspective.

Try Goldie Blox to augment your kids’ Lego collection or as an alternative. If nothing else, watch their video featuring a Rube Goldberg inspired “Princess Machine!”

IQIM is heavily involved w/ Project Scientist which is a great program for young girls with an aptitude and interest in STEM.

The tragic reality is that A.K. is going to spend her next decade being pushed away from STEM. Don’t get me wrong, she’s lucky to have encouraging parents who are preempting this push, but they will be competing with the sway of the media and her peers.

The tragic reality is that A.K. is going to spend her next decade being pushed away from STEM. Don’t get me wrong, she’s lucky to have encouraging parents who are preempting this push, but they will be competing with the sway of the media and her peers.

![(a) Two entangled Posner clusters. Each dot is a P-31 nuclear spin, and each dashed line represents a singlet pair. (b) Many entangled Posner clusters. [From the paper]](jpg/fisher-figure1f8b.jpg?w=584&h=219)