Imagine a billiard ball bouncing around on a pool table. High-school level physics enables us to predict its motion until the end of time using simple equations for energy and momentum conservation, as long as you know the initial conditions – how fast the ball is moving at launch, and in which direction.

What if you add a second ball? This makes things more complicated, but predicting the future state of this system would still be possible based on the same principles. What about if you had a thousand balls, or a million? Technically, you could still apply the same equations, but the problem would not be tractable in any practical sense.

Thermodynamics lets us make precise predictions about averaged (over all the particles) properties of complicated, many-body systems, like millions of billiard balls or atoms bouncing around, without needing to know the gory details. We can make these predictions by introducing the notion of probabilities. Even though the system is deterministic – we can in principle calculate the exact motion of every ball – there are so many balls in this system, that the properties of the whole will be very close to the average properties of the balls. If you throw a six-sided die, the result is in principle deterministic and predictable, based on the way you throw it, but it’s in practice completely random to you – it could be 1 through 6, equally likely. But you know that if you cast a thousand dice, the average will be close to 3.5 – the average of all possibilities. Statistical physics enables us to calculate a probability distribution over the energies of the balls, which tells us everything about the average properties of the system. And because of entropy – the tendency for the system to go from ordered to disordered configurations, even if the probability distribution of the initial system is far from the one statistical physics predicts, after the system is allowed to bounce around and settle, this final distribution will be extremely close to a generic distribution that depends on average properties only. We call this the thermal distribution, and the process of the system mixing and settling to one of the most likely configurations – thermalization.

For a practical example – instead of billiard balls, consider a gas of air molecules bouncing around. The average energy of this gas is proportional to its temperature, which we can calculate from the probability distribution of energies. Being able to predict the temperature of a gas is useful for practical things like weather forecasting, cooling your home efficiently, or building an engine. The important properties of the initial state we needed to know – energy and number of particles – are conserved during the evolution, and we call them “thermodynamic charges”. They don’t actually need to be electric charges, although it is a good example of something that’s conserved.

Let’s cross from the classical world – balls bouncing around – to the quantum one, which deals with elementary particles that can be entangled, or in a superposition. What changes when we introduce this complexity? Do systems even thermalize in the quantum world? Because of the above differences, we cannot in principle be sure that the mixing and settling of the system will happen just like in the classical cases of balls or gas molecules colliding.

It turns out that we can predict the thermal state of a quantum system using very similar principles and equations that let us do this in the classical case. Well, with one exception – what if we cannot simultaneously measure our critical quantities – the charges?

One of the quirks of quantum mechanics is that observing the state of the system can change it. Before the observation, the system might be in a quantum superposition of many states. After the observation, a definite classical value will be recorded on our instrument – we say that the system has collapsed to this state, and thus changed its state. There are certain observables that are mutually incompatible – we cannot know their values simultaneously, because observing one definite value collapses the system to a state in which the other observable is in a superposition. We call these observables noncommuting, because the order of observation matters – unlike in multiplication of numbers, which is a commuting operation you’re familiar with. 2 * 3 = 6, and also 3 * 2 = 6 – the order of multiplication doesn’t matter.

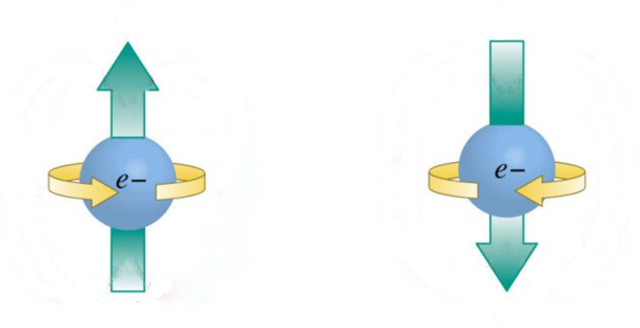

Electron spin is a common example that entails noncommutation. In a simplified picture, we can think of spin as an axis of rotation of our electron in 3D space. Note that the electron doesn’t actually rotate in space, but it is a useful analogy – the property is “spin” for a reason. We can measure the spin along the x-,y-, or z-axis of a 3D coordinate system and obtain a definite positive or negative value, but this observation will result in a complete loss of information about spin in the other two perpendicular directions.

If we investigate a system that conserves the three spin components independently, we will be in a situation where the three conserved charges do not commute. We call them “non-Abelian” charges, because they enjoy a non-Abelian, that is, noncommuting, algebra. Will such a system thermalize, and if so, to what kind of final state?

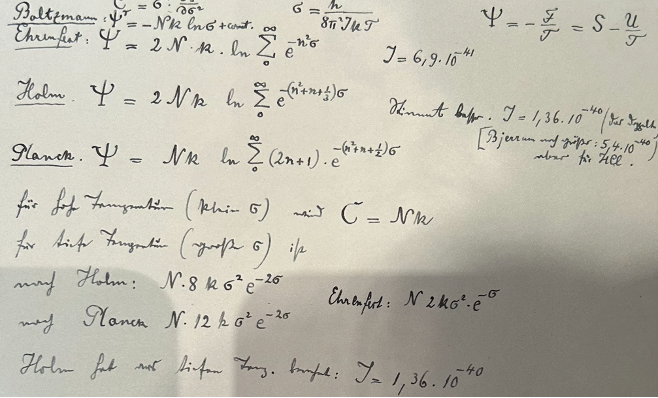

This is precisely what we set out to investigate. Noncommutation of charges breaks usual derivations of the thermal state, but researchers have managed to show that with non-Abelian charges, a subtly different non-Abelian thermal state (NATS) should emerge. Myself and Nicole Yunger Halpern at the Joint Center for Quantum Information and Computer Science (QuICS) at the University of Maryland have collaborated with Amir Kalev from the Information Sciences Institute (ISI) at the University of Southern California, and experimentalists from the University of Innsbruck (Florian Kranzl, Manoj Joshi, Rainer Blatt and Christian Roos) to observe thermalization in a non-Abelian system – and we’ve recently published this work in PRX Quantum .

The experimentalists used a device that can trap ions with electric fields, as well as manipulate and read out their states using lasers. Only select energy levels of these ions are used, which effectively makes them behave like electrons. The laser field can couple the ions in a way that approximates the Heisenberg Hamiltonian – an interaction that conserves the three total spin components individually. We thus construct the quantum system we want to study – multiple particles coupled with interactions that conserve noncommuting charges.

We conceptually divide the ions into a system of interest and an environment. The system of interest, which consists of two particles, is what we want to measure and compare to theoretical predictions. Meanwhile, the other ions act as the effective environment for our pair of ions – the environment ions interact with the pair in a way that simulates a large bath exchanging heat and spin.

If we start this total system in some initial state, and let it evolve under our engineered interaction for a long enough time, we can then measure the final state of the system of interest. To make the NATS distinguishable from the usual thermal state, I designed an initial state that is easy to prepare, and has the ions pointing in directions that result in high charge averages and relatively low temperature. High charge averages make the noncommuting nature of the charges more pronounced, and low temperature makes the state easy to distinguish from the thermal background. However, we also show that our experiment works for a variety of more-arbitrary states.

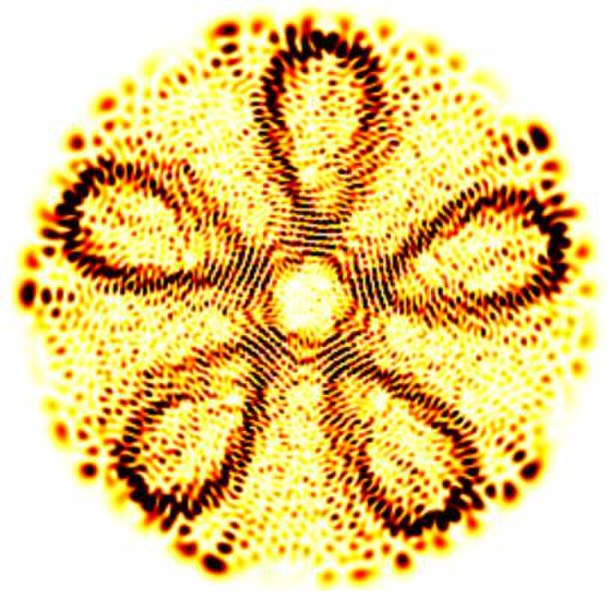

We let the system evolve from this initial state for as long as possible given experimental limitations, which was 15 ms. The experimentalists then used quantum state tomography to reconstruct the state of the system of interest. Quantum state tomography makes multiple measurements over many experimental runs to approximate the average quantum state of the system measured. We then check how close the measured state is to the NATS. We have found that it’s about as close as one can expect in this experiment!

And we know this because we have also implemented a different coupling scheme, one that doesn’t have non-Abelian charges. The expected thermal state in the latter case was reached within a distance that’s a little smaller than our non-Abelian case. This tells us that the NATS is almost reached in our experiment, and so it is a good, and the best known, thermal state for the non-Abelian system – we have compared it to competitor thermal states.

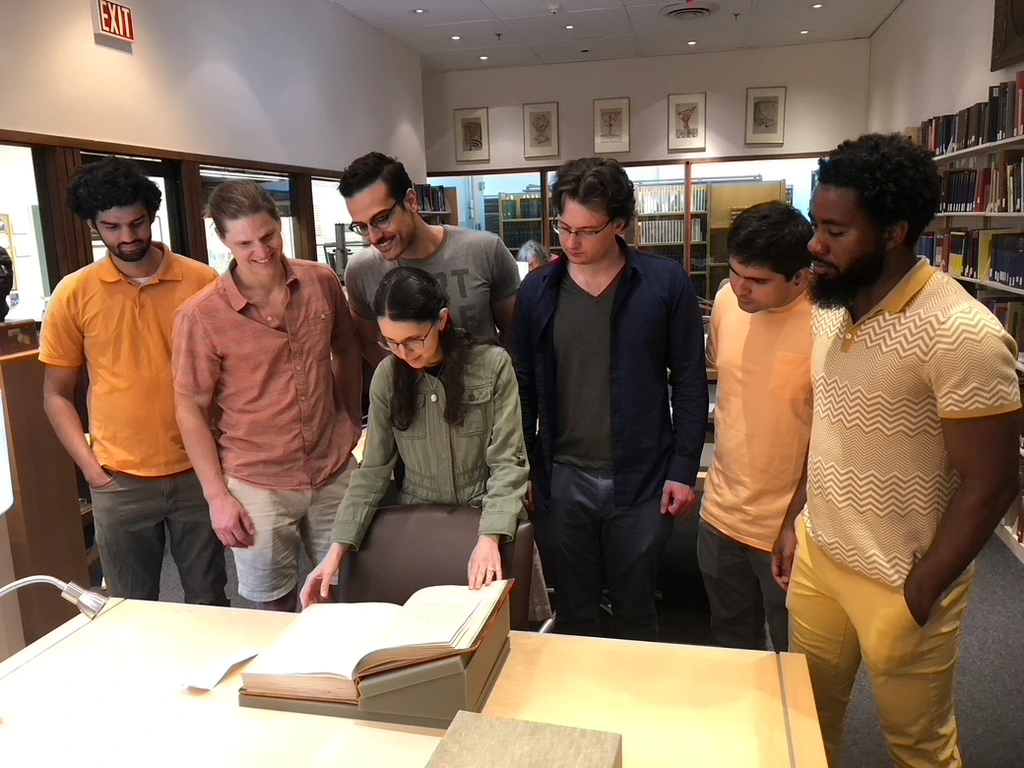

Working with the experimentalists directly has been a new experience for me. While I was focused on the theory and analyzing the tomography results they obtained, they needed to figure out practical ways to realize what we asked of them. I feel like each group has learned a lot about the tasks of the other. I have become well acquainted with the trapped ion experiment and its capabilities and limitation. Overall, it has been great collaborating with the Austrian group.

Our result is exciting, as it’s the first experimental observation within the field of non-Abelian thermodynamics! This result was observed in a realistic, non-fine-tuned system that experiences non-negligible errors due to noise. So the system does thermalize after all. We have also demonstrated that the trapped ion experiment of our Austrian friends can be used to simulate interesting many-body quantum systems. With different settings and programming, other types of couplings can be simulated in different types of experiments.

The experiment also opened avenues for future work. The distance to the NATS was greater than the analogous distance to the Abelian system. This suggests that thermalization is inhibited by the noncommutation of charges, but more evidence is needed to justify this claim. In fact, our other recent paper in Physical Review B suggests the opposite!

As noncommutation is one of the core features that distinguishes classical and quantum physics, it is of great interest to unravel the fine differences non-Abelian charges can cause. But we also hope that this research can have practical uses. If thermalization is disrupted by noncommutation of charges, engineered systems featuring them could possibly be used to build quantum memory that is more robust, or maybe even reduce noise in quantum computers. We continue to explore noncommutation, looking for interesting effects that we can pin on it. I am currently working on verifying the workings of a hypothesis that explains when and why quantum systems thermalize internally.