I’m not sure what covers more ground when I go for a long run — my physical body or my metaphorical mind? Chew on that one, zen scholar! Anyways, I basically wrote the following post during my most recent run, and I also worked up an agressive appetite for Ben and Jerry’s ice cream. I’m going to reward myself after writing this post by devouring a pint of “half-baked” brown-kie ice cream (you can’t find this stuff in your local store.)

The goal of this series of blog posts is to explain quantum teleportation and how Caltech built a machine to do this. The tricky aspect is that there are two foundational elements of quantum information that need to be explained first — they’re both phenomenally interesting in their own right, but substantially subtler than a teleportation device, so the goal with this series is to explain qubits and entanglement at a level which will allow you to appreciate what our teleportation machine does (and after explaining quantum teleportation, hopefully some of you will be motivated to dive deeper into the subtleties of quantum information.) This post will explain entanglement.

Before explaining entanglement, I want to remind you that a qubit is a superposition of two states: It’s not exclusively in either state, it’s still in limbo, with a proclivity towards each of its two possible states governed by probabilities:

and

such that

. The qubit chooses between the two states when it’s measured for the first time.

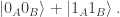

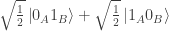

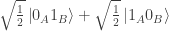

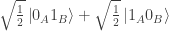

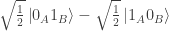

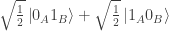

In a nutshell, entanglement is the idea that there can be non-classical correlations between qubits. We can generate entangled pairs of qubits, such as where the subscripts stand for Alice and Bob, respectively. They each get one qubit. Now, setting

and

, we can look back at the previous paragraph to see what we expect to get after measuring this state’s two qubits: with probability 1/2, Alice and Bob’s qubits are in the state

(cookies), and with probability 1/2 their qubits are in the state

(brownies). The important thing is that their qubits always agree in this special quantum state (remember, the state

is really the two-qubit state

and, similarly, the state

is actually the state

). So, if Alice measures first, and then Bob second, with probability one, they will get the same outcome. The same is true if Bob measures first or if they measure at the same time. They always either both have cookies or both have brownies. However, similar to before (see Intro to qubits), something special happens when the first measurement is performed. Before that point, the qubits haven’t yet made up their mind about whether to be cookies or brownies. After a measurement, Alice and Bob are left with either both cookies or both brownies. Returning to our notation, the wavefunction

has collapsed to either

or

In some sense, this is our first taste of teleportation. It’s subtle, but when Alice performs a measurement on her qubit in the entangled pair

, she instantaneously alters Bob’s qubit to match hers no matter how far apart their qubits are!

I also want to mention that after creating qubits, the coefficients (related to probabilities) aren’t permanently fixed. We can perform unitary operations (rotations in a mathematical space where distances and angles between objects exist), which alter the probabilities of whether Alice and Bob will both have cookies or both have brownies. This is similar to performing logical operations on bits in a computer. For example, a bit flip takes 0 -> 1 and 1 -> 0 and is called a NOT gate. A NOT gate is actually a simple unitary operation: If the 0 is the north pole of a sphere and the 1 is the south pole, then the NOT gate is a rotation that takes the north pole to the south pole and the south pole to the north pole. Our quantum teleportation protocol, and quantum computation more generally, fundamentally rely upon these unitary operations, where qubits are represented by vectors pointing at the surface of three-dimensional spheres (see Bloch sphere) and unitary operations act as rotations on these spheres.

In an attempt to be concrete, let’s assume that Alice and Bob start off on Earth at Caltech’s IQIM, where they generate an entangled state (quantum brown-kies in their respective refrigerators). Bob then spends a few months flying to Mars (my Caltech/JPL friends who had to wait for the Mars Science Laboratory to make this journey sympathize with Bob. Unfortunately, I’m not cool enough to be friends with the Mohawk Guy.) The distance between Mars and Earth obviously varies, but on average it takes about ten minutes for light to travel between the two. After Bob is safely settled on Mars (with the help of JPL of course), let’s say that Alice and Bob coordinate so that Alice will reach into her refrigerator and pull out her dessert and then Bob will do so moments later (in the appropriate reference frame, because we’re starting to get relativistic.) They then send signals to each other documenting which dessert they obtained. Ten minutes later, they will learn that they each grabbed the same dessert. They always grab the same dessert.

The idea of quantum teleportation is that we can use entanglement and the transmission of classical information (bits) to move quantum information (qubits) between labs. Quantum teleportation does NOT allow us to send usable information faster than the speed of light. It’s like locking a time capsule that can only be opened years in the future — the quantum information is already on Mars waiting for Bob after Alice measures her entangled qubit, but it’s inaccessible until enough time passes (which is ultimately governed by the speed of light.) Bob can’t ‘decode’ the quantum information that Alice sent until after he has received classical bits describing the measurement outcome that Alice obtained in her lab on Earth. The power of quantum teleportation is that we can break the important and hard problem of how to transmit quantum information (a complete description of a quantum system) into two easier to solve sub-problems — how to spread entanglement (lasers are one way) and how to send classical information (oftentimes lasers, again.) My next post will explain this protocol in detail.

Another future post in this series will explain how we actually build entangled qubits. Here are two loose examples to keep in mind in the interim: we can generate pairs of photons (particles of light) which must have either the same or opposite polarizations. Another example could include pairs of atoms which have the same nuclear spin, along some predetermined axis. You can imagine a particle decay process where conservation laws say that two sub-particles must have the same spin, but that whether they are both up or down depends on the spin of the original particle, whose spin might have been prepared in a superposition itself.

To summarize, we have seen that qubits are superpositions of two-state systems and have introduced entanglement as a universal resource that allows the measurement of one qubit to affect the state of another, instantaneously. Now, we are finally ready to tackle quantum teleportation… which I’ll do in my next post. For now, I’ll leave you with a skeleton of the teleportation schema:

Mission: Transmit an arbitrary bit of quantum information (qubit) between two distant laboratories using only an easy-to-generate entangled pair (such as an EPR pair) and two bits of classical communication (“00”, “01”, “10”, “11”).

Step 0: Two physicists, Alice and Bob, set up distant laboratories from which they will perform quantum teleportation.

Step 1: They generate entangled states at one of the labs.

Step 2: They spread these states between their laboratories.

Step 3: Alice performs an operation.

Step 4: Alice performs a measurement.

Step 5: Alice makes a phone call to Bob.

Step 6: Bob performs an operation.

Step 7: Bob now has Alice’s qubit.

In conclusion, Quantum teleportation allows Alice and Bob to send quantum information between distant laboratories using only classical information and generic entanglement (which could have been generated ahead of time.) Maybe someday you’ll be able to send the full description of some piece of electronics to a distant 3D printer and have a duplicate printed there — not just a duplicate of the ‘off’ mode of the electronics, but its exact current state. Or a research group in Pasadena will be able to send the complete description of a new material to collaborators in Vienna. Maybe even someday this will penetrate to biology. Maybe we’ll even generate a reservoir of entanglement by shining a laser onto a distant asteroid. My next post will describe the quantum teleportation protocol and its applications more thoroughly. For now, I’m going to enjoy my Ben and Jerry’s (I’ll get off this schtick soon enough.)

Nice article!

In your teleportation example, would Bob be performing the same operations that Alice did? If yes, wont the results of both be different?

Looking forward for you Teleportation application post.

I think the operation that Bob does refers to the decoding of the quantum information after he gets the necessary classical information from Alice’s phone call.

Sankalp, in that teleportation example, Alice and Bob share an entangled pair of qubits which is initially in the state When EITHER of them measure(observe) this entangled pair for the first time, the entangled pair collapses to the state

When EITHER of them measure(observe) this entangled pair for the first time, the entangled pair collapses to the state  OR

OR  . This means that if Alice measures first and obtains

. This means that if Alice measures first and obtains  then so will Bob, because their entangled pair is in the state

then so will Bob, because their entangled pair is in the state  . The collapse of the wavefunction happens instantaneously — if Alice were to measure on Earth, and then Bob on mars only moments later, they would obtain the same result (even though it would take ten minutes for light to travel between Mars and Earth allowing them to confirm that they obtained the same values.)

. The collapse of the wavefunction happens instantaneously — if Alice were to measure on Earth, and then Bob on mars only moments later, they would obtain the same result (even though it would take ten minutes for light to travel between Mars and Earth allowing them to confirm that they obtained the same values.)

I read that entangled pairs are always opposite to each other. If that is true then why do you say that Bob and Alice see the exact same thing? That’s the only thing I was a bit confused about.

There is a kind of entangled pair in which the results are always opposite each other. There is also a kind of entangled pair, as described by this article, in which the results are always identical. In fact, there are infinitely many non-equivalent kinds of entangled pairs. In order to perform actual calculations or describe an example explicitly, you have to specify precisely what sort of entangled pair you have, but the essential thing is just to have any fully entangled pair at all, since it is possible to convert any one fully entangled pair to any other by a straightforward unitary operation at just one of the laboratories. This is why two-way entanglement can be thought of as a resource, measured by the equivalent number of fully entangled pairs.

Well said and thanks for doing my job for me 🙂

Oh I see, I had the wrong idea about entanglement this whole time. Thank you for the answer.

Got it. That’s a great question and it clarifies Sankalp’s comment as well. You’re right, in my post, the examples I used for entangled pairs involved qubits that would always be opposite to each other. In general, whether Alice and Bob’s qubits are always opposite or always equal depends on how the entangled pair was generated. For example, as a thought experiment, our entangled pair could be generated by a spin 1 particle which decays to two spin 1/2 particles. If the original particle had spin +1, then it would decay to two spin +1/2 particles. If the original particle had spin -1, then it would decay to two spin -1/2 particles. If we used a process like this to generate our entangled pair, then Alice and Bob’s qubits would always agree.

I shouldn’t have used the word spin because that’s very misleading, but keep this in mind as a process where there are different decay modes and conservation laws in effect!

Thank You (everyone) very much for clearing that up.

Thanks. That cleared things up.

What does the phone call (step 5 in your schematic do)? What if the phone call was not made?

The phone call is necessary for the teleportation to work correctly. Without it, Bob would not know how to measure his qubit properly and would get a random result, though the state of his qubit had changed to reflect the teleportation of information from Alice. Shaun will be posting the third part of his teleportation saga soon! Details about the phone call will be in there.

I like your article on teleportation and am looking forward to seeing you next. I have question not closely related to this but who knows, maybe you do.On which branes are quarks and leptons

found on the Rundal-Sundram model. I think

am getting confused by all the crackpots.

shaunmaguire wrote (August 19, 2012):

> […] let’s assume that Alice and Bob start off on Earth at Caltech’s IQIM, where they generate an entangled state (quantum brown-kies in their respective refrigerators).

I wonder whether along with the “brown-kie” state ‘$\alpha \left|0\right> + \beta \left|1\right>$’, with ‘$|\alpha|^2 + |\beta|^2 = 1$’ and ‘$0 < |\alpha|^2 – \alpha \left|1\right>$’ (the “coo-ie” state) as well;

and/or along with state ‘$\sqrt{\frac{1}{2}\left|0_A 0_B\right> + \sqrt{\frac{1}{2}\left|1_A 1_B\right>$’ also states ‘$\sqrt{\frac{1}{2}\left|0_A 0_B\right> – \sqrt{\frac{1}{2}\left|1_A 1_B\right>$’ or ‘$\sqrt{\frac{1}{2}\left|0_A 1_B\right> + \sqrt{\frac{1}{2}\left|1_A 0_B\right>$’ or ‘$\sqrt{\frac{1}{2}\left|0_A 1_B\right> – \sqrt{\frac{1}{2}\left|1_A 0_B\right>$’.

> Bob then spends a few months flying to Mars […]

How might be determined whether Alice and Bob kept “quantum brown-kies in their respective refrigerators” while they were separated from each other (i.e. instead of one, or the other, or both changing into “quantum coo-ies”)

and/or whether Alice’s and Bob’s joint state remained ‘$\sqrt{\frac{1}{2}\left|0_A 0_B\right> + \sqrt{\frac{1}{2}\left|1_A 1_B\right>$’ instead, for instance, of changing into ‘$\sqrt{\frac{1}{2}\left|0_A 1_B\right> + \sqrt{\frac{1}{2}\left|1_A 0_B\right>$’ ?

Oops — sorry, there’s no comment preview.

So what’s the correct syntax for writing formulas in comments (such as in https://quantumfrontiers.com/2012/08/19/how-to-build-a-teleportation-machine-intro-to-entanglement/comment-page-1/#comment-209 ), please?

Frank Wappler wrote (August 28, 2012 at 2:24 pm):

> So what’s the correct syntax for writing formulas in comments […], please?

While apparently noone has replied to my request yet, perhaps I may be permitted meanwhile to try and help myself by using this followup as a sandbox:

1. Without delimiters:

\beta \left|0\right> – \alpha \left|1\right>

2. “bb code” delimiters:

3. Variation of “stack exchange”-style delimiters:

$$\beta \left|0\right> – \alpha \left|1\right>$$

Frank Wappler wrote (August 29, 2012 at 10:46 am):

> […] perhaps I may be permitted meanwhile to try and help myself by using this followup as a sandbox: 1. […]

Continued:

4. A delimiter style shown at http://en.forums.wordpress.com/topic/latex-problem :

Alright — the delimiters “$latex … $” seem to work.

Now just to be sure whether plain “less than”-signs may be used within:

This is a test: $\alpha\beta=\gamma$.

$$ E=mc^2 $$

And .

.

Yup and

Great post!

There is one thing that may be misunderstood:

Quantum teleportation passes only the quantum information, and not the system in which the information is stored. This is exactly the same as what happens when a file is sent over the internet: only the bits are passed around, and not chunks of the hard drive that stores the file.

The following sentence may lead to a different conclusion: “Maybe someday you’ll be able to send the full description of some piece of electronics to a distant 3D printer and have a duplicate printed there — not just a duplicate of the ‘off’ mode of the electronics, but its exact current state.”

shaunmaguire wrote (August 19, 2012):

> […] let’s assume that Alice and Bob start off on Earth at Caltech’s IQIM, where they generate an entangled state (quantum brown-kies in their respective refrigerators).

I wonder whether along with the “brown-kie” state , with

, with  and

and  (the “coo-ie” state) as well;

(the “coo-ie” state) as well;

and/or along with state also states

also states  or

or  or

or  .

.

> Bob then spends a few months flying to Mars […]

How might be determined whether Alice and Bob kept “quantum brown-kies in their respective refrigerators” while they were separated from each other (i.e. instead of the contents of one, or the other, or both refrigerators changing into “quantum coo-ies”) ?;

and/or whether Alice’s and Bob’s joint state remained instead, for instance, of changing into

instead, for instance, of changing into  ?

?

Frank Wappler wrote (August 29, 2012 at 12:08 pm):![\sqrt{\frac{1}{2} [...]](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5Csqrt%7B%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B2%7D+%5B...%5D&bg=ffffff&fg=333333&s=0&c=20201002)

> […]

Well — wouldn’t it be nice/efficient to have a comment preview function ?!?

So once again:

shaunmaguire wrote (August 19, 2012):

> […] let’s assume that Alice and Bob start off on Earth at Caltech’s IQIM, where they generate an entangled state (quantum brown-kies in their respective refrigerators).

I wonder whether along with the “brown-kie” state , with

, with  and

and  (the “coo-ie” state) as well;

(the “coo-ie” state) as well;

and/or along with state also states

also states  or

or  or

or  .

.

> Bob then spends a few months flying to Mars […]

How might be determined whether Alice and Bob kept “quantum brown-kies in their respective refrigerators” while they were separated from each other (i.e. instead of the contents of one, or the other, or both refrigerators changing into “quantum coo-ies”) ?;

and/or whether Alice’s and Bob’s joint state remained instead, for instance, of changing into

instead, for instance, of changing into  ?

?

I just noticed that my comment (August 29, 2012 at 12:21 pm) in the section between

>

and

>

still came out garbled;

in the next and hopefully final iteration I’m going to replace the “less than” signs in the formula(s) with “\lt” …

Frank Wappler wrote (on August 29, 2012 at 12:34 pm):

> […] in the next and hopefully final iteration I’m going to replace the “less than” signs in the formula(s) with “\lt” …

That was presuming it would parse: …

…

Frank Wappler wrote (on August 29, 2012 at 12:34 pm):

> […] in the next and hopefully final iteration I’m going to replace the “less than” signs in the formula(s) with “\lt” …

Well — according to this

Click to access symbols-a4.pdf

the “\lt” (which I seem to’ve gotten used to somewhere else) isn’t supposed to work by default at all. But perhaps “\less” ?:

shaunmaguire wrote (August 19, 2012):

> […] let’s assume that Alice and Bob start off on Earth at Caltech’s IQIM, where they generate an entangled state (quantum brown-kies in their respective refrigerators).

I wonder whether along with the “brown-kie” state , with

, with  and

and  there ought to be considered a state

there ought to be considered a state  (the “coo-ie” state) as well;

(the “coo-ie” state) as well;

and/or along with state also states

also states  or

or  or

or  .

.

> Bob then spends a few months flying to Mars […]

How might be determined whether Alice and Bob kept “quantum brown-kies in their respective refrigerators” while they were separated from each other (i.e. instead of the contents of one, or the other, or both refrigerators changing into “quantum coo-ies”) ?;

and/or whether Alice’s and Bob’s joint state remained instead, for instance, of changing into

instead, for instance, of changing into  ?

?

Frank Wappler wrote (August 29, 2012 at 12:37 pm): , with […]

, with […] (the “coo-ie” state) as well;

(the “coo-ie” state) as well;

> […] the “brown-kie” state

> […] a state

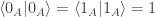

Especially relevant is of course the inner product of these two states (for clarity here those of Alice):

Provided that the states and

and  are supposed to be orthonormal,

are supposed to be orthonormal,

,

,

,

,

then

This vanishes for certain pairs of complex numbers and

and  (e.g. if they’re both real numbers), but not in general.

(e.g. if they’re both real numbers), but not in general.

A (still normalized) “coo-ie” state which is manifestly orthogonal to the “brown-kie” state would be instead:

Frank Wappler wrote (August 30, 2012 at 1:46 pm):

> […]

Sandbox mode again.

(How’s that comment preview coming along, btw. ?. &)

Frank Wappler wrote (August 30, 2012 at 1:57 pm):

> […]

Sandbox mode continued:

Frank Wappler wrote (August 29, 2012 at 12:37 pm): , with […]

, with […] (the “coo-ie” state) as well;

(the “coo-ie” state) as well;

> […] the “brown-kie” state

> […] a state

Especially relevant is of course the inner product of these two states (for clarity here those of Alice):

Provided that the states and

and  are supposed to be orthonormal,

are supposed to be orthonormal,

,

,

,

,

then

This vanishes for certain pairs of complex numbers and

and  (e.g. if they’re both real numbers), but not in general.

(e.g. if they’re both real numbers), but not in general.

A (still normalized) “coo-ie” state which is manifestly orthogonal to the “brown-kie” state would be instead:

Another way to express a (normalized) “coo-ie” state would be

which is defined even if .

.

Is it possible to give an expression of a normalized state orthogonal to the the “brown-kie” state which is is defined even if

which is is defined even if  as well as even if instead

as well as even if instead  ?

?

Shaun,

I’m following the math but it’s not my field, as such i’m not always sure how to verbally restate the equations and figures. Could you provide any lingo or ‘read as:’ along with the equations where appropriate?

It would be helpful to those of us in different fields who want to research things more based on your article but are having google and other search engines fail in regex parsing.

your hacker friend.

PS – we miss you in Arlington 😉

Pingback: The maths of the spirograph… with the drawings « cartesian product

Pingback: How to build a teleportation machine: Teleportation protocol | Quantum Frontiers

Pingback: “Nature, you instruct me.” | Quantum Frontiers

Pingback: The Story of Energy: The Physics of an Atom, Part 1 | Florida State Tribune

Pingback: Guns versus butter in quantum information | Quantum Frontiers

What are the operations specified in step 3 and 6?

Hi, its pleasant post about media print, we all be familiar with media is a

impressive source of facts.